Researcher name:

Michael Andrews, Masters in Teaching Secondary Education Student, History Major

Credentials:

Bachelor’s in history from Western Washington University, Attending Woodring College of

Education to become a secondary school teacher

Focus: The Ottoman Empire, French/British goals with the Ottoman territories

1.The Ottoman Empire

2.French/British Goals

Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

Directed by: David Lean

Summary: “Due to his knowledge of the native Bedouin tribes, British Lieutenant T.E. Lawrence (Peter O'Toole) is sent to Arabia to find Prince Faisal (Alec Guinness) and serve as a liaison between the Arabs and the British in their fight against the Turks. With the aid of native Sherif Ali (Omar Sharif), Lawrence rebels against the orders of his superior officer and strikes out on a daring camel journey across the harsh desert to attack a well-guarded Turkish port.”

Part I: The Ottoman Empire (1683-1918)

1. The Sick Man of Europe, The Eastern Question, Ottoman Height, and Decline

The Sick Man of Europe

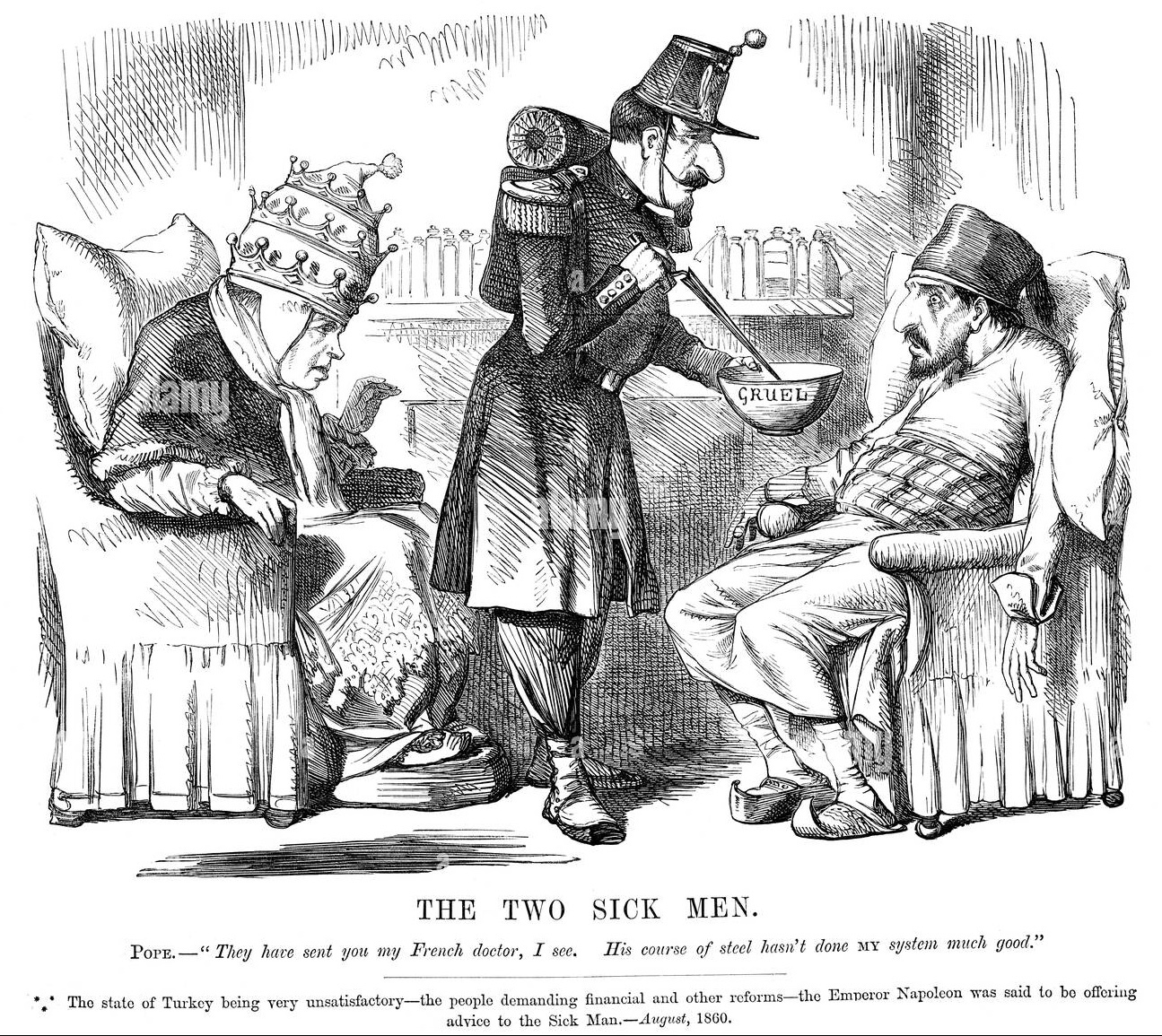

The Russian Emperor Nicholas I of the Russian Empire described the Ottoman Empire as a “Sick Man”, the believed first use of the term that began in the mid-1800s (1833). To give us further background and context to why this term was applied to the Ottoman Empire, we must look at the Eastern Question – the issue of the overall instability of the Ottoman Empire from the late 1700s to the early 1900s.

To safeguard their military, political, and economic interests in and around the Ottoman Empire, the Great Powers of Europe (especially Great Britain and Russia) saw the decline or preservation of the Ottoman state as paramount to power in the east. Russia stood by to gain from a declining Empire whereas Great Britain before WWI sought to keep it alive.

The height of Ottoman Empire is often classified, seemingly contradictorily, with the defeat of the Ottomans outside of Vienna in 1683. Many Central European possessions were then ceded to Poland-Lithuania and Austria in 1699. Russia saw an opportunity to become the dominant power in the region in the early 1800s and other European powers wished to curb this imperialist push from Russia. This would result in such conflicts between Europeans over Ottoman statehood like the Crimean War.

Between 1693 and 1914, the Ottoman empire faced a period of reliefs and setbacks. During the Napoleonic Era, Napoleon’s French Empire distracted the Russian attention towards the Ottomans and provided some relief. After a failed Russo-French alliance that promised to partition Ottoman European holdings, Napoleon was to be defeated by a coalition of European powers and the Ottoman Empire, while not picked apart, was left out of European affairs.

The Eastern Question

Between 1804-1815, the Serbian revolution made way for the complete construction of the modern Serbian state between 1815-1833. The Greek War of Independence in 1821 saw the coined term “The Eastern Question” first used and saw European powers reluctant to join the fight to free Greece because the Concert of Europe (an uneasy peace in Europe post-Napoleon) was to be kept and upheld. With the death of Alexander I of Russia, Nicholas I took the throne and decided to act decisively and aid Greece, causing Great Britain to join to prevent Greece from becoming a Russian puppet. The Greek War stood as a proxy so that Russia could pull more out from the Sultan of the Ottomans, including Black Sea territory and access to trade through the Dardanelles.

Muhammad Ali decided to kick off a revolt in Egypt just as the Greek War ended in 1831-1832. As common with Russian intentions at this time to reduce the Ottoman Empire into a vassal state, Russia supported Ali in Egypt. The Russians helped negotiate complete dominance over the Empire – promising to protect the Ottomans, but also able to open and close the Dardanelles whenever Russia was a t war. France and Great Britain were not happy with this Russian expansionism. Britain and Russia helped make a peace between Ali and the Ottoman Empire and allowed Ali to rule over Egypt virtually independently. The Ottomans, by the 1840s, became known as the “sick man of Europe” and its downfall appeared inevitable.

2. The Crimean War, Great Eastern Crisis, German Relations, Young Turks, Bosnian Crisis

Crimean War

The Crimean War began in the 1850s primarily due to religious reasons. Because of old treaties made in the 1700s, France was to protect all Roman Catholics in the Ottoman Empire and Russia was to protect all Orthodox Christians. Monks from both parties clashed over the ownership of churches in Palestine and the ottoman Sultan moved to help the Roman Catholic side.

The Russians attempted to get the Sultan to sign a treaty that would allow Russian intervention in Ottoman affairs whenever they were deemed inadequate, but skillful British diplomacy prevented this and sparked a Russian military response into Eastern European territories held by the Ottoman Empire.

Britain and France deployed their fleets to protect the Ottomans but wished for a diplomatic solution. This broke down after the Ottoman Sultan rejected any diplomacy after feeling it was left too open to interpretation and attacked the Russian army on the Danube. The Russian fleet destroyed the Ottoman fleet at Sinope in 1853 and France and Britain declared war on Russia shortly after Russia ignored warnings to back down.

“France takes Algeria from Turkey, and almost every year England annexes another Indian principality: none of this disturbs the balance of power; but when Russia occupies Moldavia and Wallachia, albeit only temporarily, that disturbs the balance of power. France occupies Rome and stays there several years during peacetime: that is nothing; but Russia only thinks of occupying Constantinople, and the peace of Europe is threatened. The English declare war on the Chinese, who have, it seems, offended them: no one has the right to intervene; but Russia is obliged to ask Europe for permission if it quarrels with its neighbor. England threatens Greece to support the false claims of a miserable Jew and burns its fleet: that is a lawful action; but Russia demands a treaty to protect millions of Christians, and that is deemed to strengthen its position in the East at the expense of the balance of power. We can expect nothing from the West but blind hatred and malice...” (comment in the margin by Nicholas I: ‘This is the whole point’).

— Mikhail Pogodin's memorandum to Nicholas I

Despite withdrawal from the Danube, Britain and France continued the war to halt Russian expansionism deemed too hostile to be left alone and to protect the Ottoman Empire as a buffer state against Russia for the future. The Great Powers were eventually successful in making peace and made Russia adhere to withdrawing its hold over the Danube and ridding any and all warships from all powers in the Black Sea. Most notably, all the Great Powers, including Russia, pledged to protect the sovereignty and integrity of the Ottoman Empire.

This Treaty of Paris, as it was called, dissolved in 1871 once the French Third Republic was established after the Franco-Prussian War and France grew disinterested in maintaining Ottoman integrity. Britain could not enforce the treaty on their own, and so Russia denounced the Black Sea clause and established a Black Sea fleet once again.

The Great Eastern Crisis

In 1875, the Ottoman troubles began once again with the revolt of Herzegovina and the Bulgarian Rebellion shortly after. Peace was attempted by the Great Powers but failed because Ottoman internal politics saw instability in leadership. The treasury was empty, and Serbia/Montenegro continued to revolt. By 1876, these revolts were mostly put down, but Europeans were shocked by rumors of Ottoman brutality during these uprisings.

Russian intervention in rebellions saw the establishment of independent Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, and Montenegro. The Great Powers aside from Russia made sure to divide Bulgaria in two to prevent total Russian domination and Britain gained the island of Cyprus through a secret deal. Bosnia and Herzegovina were secretly transferred to Austrian control as well.

German Relations

1879 saw Germany align itself more with Austria-Hungary and farther away from Russia. It also sought to closely align itself with the Ottoman Empire. They reorganized its military and financial system while getting some commercial concessions which included construction of the Baghdad Railway. Despite Britain holding dominance in the region, Germany began aiding the Ottoman Empire through investment capital.

Young Turks Revolution

1908 saw the Young Turk political party lead a rebellion against Sultan Abdul Hamid II. The Sultan was deposed and created the Second Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire. This helped to slow the decline as reforms began to take place, but much of it was too little too late.

Bosnian Crisis

Austria-Hungary decided to annex Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1908 due to fears of Turkish resurgence after the Young Turk Revolution. Austria promised to support Russian warship access in the Dardanelles and so Russia did not oppose the annexation. Serbia was furious at this, and the annexation created abysmal relations between Austria-Hungary and Serbia.

3. Outbreak of WWI, Switch to pro-German elements, Middle Eastern Theater

Outbreak of WWI, Switch to pro-German Elements

Weakened by aforementioned political instability, rebellions and uprisings, military defeats, and civil strife, the Ottoman Empire was not well established to join a global war. The Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 saw the loss of 83% of their European holdings. The Great Powers offered financial assistance during the Balkan Wars, but the pro-German faction within the state won out and consequently the Ottomans grew closer to Germany.

Russia, France, and Great Britain had an interest in Ottoman neutrality because of their position within the Mediterranean and the Middle East strategically speaking. Multi-polarity of the two great alliances of Europe usually meant the Ottomans could survive by playing one off against the other. The pro-British faction saw some success when Austria annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina, with prominent Young Turk members being sent to London to discuss further diplomatic ties:

"Our habit was to keep our hands free, though we made ententes and friendships. It was true that we had an alliance with Japan, but it was limited to certain distant questions in the Far East.

The [Ottoman delegate] replied that Empire was the Japan of the Near East (alluding to Meiji Restoration period which spanned from 1868 to 1912), and that we already had the Cyprus Convention which was still in force.

I said that they had our entire sympathy in the good work they were doing in the Empire; we wished them well, and we would help them in their internal affairs by lending them men to organise customs, police, and so forth, if they wished them.[13]

— Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon

However, British proposals started to scare off the ottoman Empire, such as the one below:

Turkey's way of assuring her independence is by an alliance with us or by an undertaking with the Triple Entente. A less risky method [he thought] would be by a treaty or Declaration binding all the Powers to respect the independence and integrity of the present Turkish dominion, which might go as far as neutralization, and participation by all the Great Powers in financial control and the application of reform.[14]

— Sir Louis du Pan Mallet

The Young Turks sought to rid themselves of European financial assistance and seek to establish themselves as independent once again. British proposals like the one above showed the Ottoman Empire that the Great Powers could not be trusted to help in the way that they wanted.

Once Archduke Franz Ferdinand was murdered in 1914 in the July Crisis, Unaware of British possibilities of entering the war, Germany promised the Ottoman Empire an anti-Russian alliance that would see the Ottomans rid of Russian influence and even regaining lost territories form the previous century or so. Two days before the outbreak of the war, the Ottomans and Germany agreed to a secret alliance against Russia. Both Britain and France rejected pro-French and pro-British attempts at making solidified military alliance. Winston Churchill asked for the requisition of two Ottoman ships being built by British shipyards. This left a bad taste in the mouth of the Ottomans, and they sought to give the ships over to Germany for a modest price. The Kaiser Wilhelm II ordered a renegotiation of the alliance to be a more serious military one.

Two German/Austrian ships were pursued to Constantinople and the Dardanelles by the British – the Turks allowed this to happen, despite them being in a binding agreement to not allow such an opening. The take over of German admirals of the Ottoman navy and German military success in 1914 saw the pro-German faction in the Empire to finally gain dominance – Ottomans would declare war on Russia shortly after. By November, the ottomans were at war with the Triple Entente in its entirety.

Middle Eastern Theater

The Ottoman Empire were forced to face the British from both Iraq and from their own doorstep of the Dardanelles. Mesopotamia had been conquered by the Ottomans in the 100s but was never completely pacified. Mesopotamia was of lower priority to the Ottomans who instead focused upon Palestine and the Caucuses more fervently. The Caucuses theater saw the Ottomans attempt to prevent Russia from accessing that region.

The Arab Revolt

The Great War in the Middle East saw groups who had been previously oppressed join the Allies so they could gain autonomy. Assyrian and Armenian volunteers joined the fight against the Ottomans and the Arab Revolt saw Arab people try and stake out a state of their own with British guarantees. This was not to be as the British reneged their promise to help create and Arab state and, instead, created mandate territories instead.

Arab nationalists since 1821 had been mostly moderate. Arabs wanted some autonomy and a change in how Arabs could be drafted during peace time. By the time of the Young Turk Revolt in 1908, pan-Turkism and a more centralized state became the goals of the Ottoman Empire. Once war broke out in 1914, Ottoman and German forces captured and tortured Arab nationalist figures.

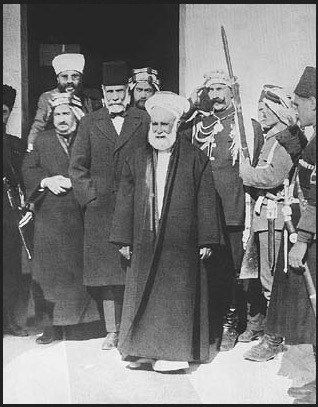

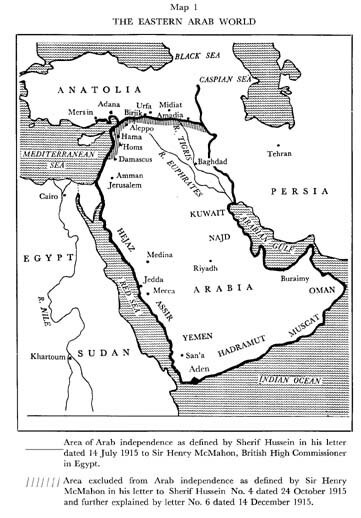

The Arabs of Hejaz and the British engaged in a deal that would guarantee support against the Ottomans in exchange for the assured creation of an Arab state. The Sharif (ruler) of Mecca/Hejaz, Hussein, decided to immediately join the Allies because of this and rumors that he was soon to be replaced by the Ottomans.

Hussein had rifles for only 10,000 of 50,000 men ready to fight from the Hejaz. In 1916, Hussein’s sons ‘Ali and Faisal began the Arab Revolt by assaulting the city of Medina. Although Medina was a failure, the Arabs were able to claim Mecca after defeating the Ottoman garrison with Anglo-Egyptian support. Ottoman artillery happened to hit several parts of Mecca, allowing for a convenient propaganda point to help get other Arabs to join the cause. Shortly after the entirety of the Red Sea port cities were captured in cooperative battles.

The Arab Revolt was eventually successful; however, as mentioned, the British and French reneged on their deal with the Arabs and portioned old Ottoman territory amongst themselves. The British eventually backed Ibn Saud in taking over what would have been the independent Arab State. The revolt is best remembered for being one of the first major organized Arab nationalist movements.

Part II: British and French Strategies

1. British Strategy

Mesopotamia

The British strategy in the Middle East involved gaining oil from conquering the Mesopotamia region of the middle East. They also sought to gain prestige in the eyes of India’s Muslim population. Arab populations fought with the British in this theater because they thought the power balance would be shaken up enough for them to be independent of Ottoman rule. However, British machinations of the region proved to be dramatically different.

Sinai and Palestine Campaign

This campaign kicked off in 1915 with an Ottoman raid against the famed Suez Canal. German-led Ottoman forces assaulted the British Protectorate of the Sinai Peninsula (Egyptian controlled), which was unsuccessful. After the dismal and shocking failure of the Gallipoli Campaign, the Egyptian Expeditionary Force formed by British veterans fought for control of Sinai with the Ottoman Fourth Army.

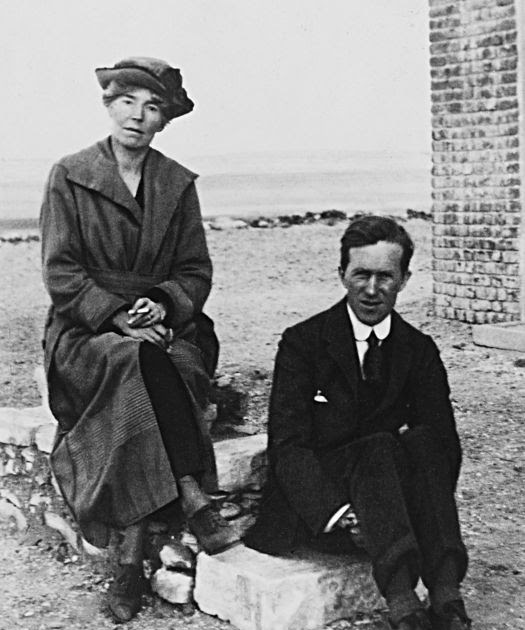

The port cities on the Red Sea were taken by Arab land forces with support from British naval forces. June of 1916 saw the British sending out several officials to aid the revolt in Hejaz. These included Colonel Cyril Wilson, Pierce C. Joyce, and Stewart Francis Newcombe. T.E. Lawrence arrived later and is often mistakenly assumed to have been the only Allied officer aiding the Arab Revolt, which was false.

Gertrude Bell, an English archaeologist, was highly prized for imperialist policy making because of her extensive knowledge of the Middle East and contact network. Her involvement is considered to have been crucial to the success of Lawrence’s occupation of Aqaba and his reliance on her reports proved critical since she had been in the Middle East since 1888. Lawrence became close with one of the Arab commanders, Faisal, but not so close with Abdullah, causing British support to heavily favor Faisal instead. Lawrence focused on railway supply attacks instead of city assaults; his greatest contribution is said to be coordinating Arab army groups to support British maneuvers in the Middle East.

General Edmund Allenby was crucial in neutralizing the Ottomans in this theater of the war, especially in 1917. By 1918, British designs for the region seemed clear – as with Mesopotamia, there was to be created several Mandates, including one for Palestine, and for Syria and Lebanon. The public did not have a great understanding of this theater of the war; indeed, they thought it a minor military action when in reality it spawned the Partitioning of the Ottoman Empire between Britain and France.

2. French Strategy

Sykes-Picot Agreement

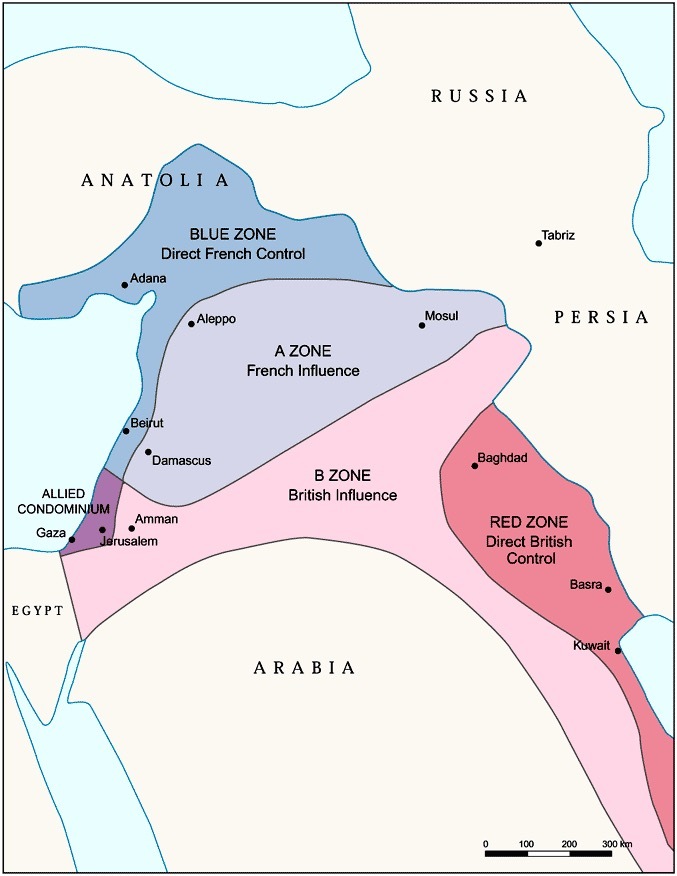

Although this could have been mentioned in the British section, the Sykes-Picot Agreement saw a secret agreement between Britain and France made in 1916. This made it so both Empires promised to define their spheres of influence and partition the ottoman Empire amongst themselves once the war ended. Outside of the Arabian Peninsula, Ottoman territories would be divided amongst both powers. French strategy largely served a supportive role to the British. Both sides would emerge from the war reneging on their deal to supply an independent state and confuse the situation further by promising Palestine to serve in the creation of a Jewish state.

Appendix I: Images

Figure 1. Expansion of the Ottoman Empire up to 1683-1699

Figure 2. "The Two Sick Men" a political cartoon showing France under Napoleon feeding the Pope and the Ottoman Empire keeping them alive. August, 1860.

Figure 3. Four French Zouaves during the Crimean War

Figure 4. The Young Turks declaring the Revolution, 1908. Featured are Greek, Muslim, and Armenian religious leaders

Figure 5. Sharif Hussein, leader of the Arab Revolt, pictured in the center

Figure 6. Gertrude Bell with T.E. Lawrence in Egypt

Figure 7. Proposed Arab State following the end of WWI with an Allied victory

Figure 8. The partition of the Middle East between France and Great Britain (The Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916)

Resources

Part I: The Ottoman Empire

Karaian, Jason; Sonnad, Nikhil (2019). "All the people, places, and things called the "sick man of Europe" over the past

160 years". Quartz.

Juan Cole, Napoleon's Egypt: Invading the Middle East (2008)

Michael S. Anderson, The Eastern Question, 1774–1923: A Study in International Relations (1966) ch 1

Walter Alison Phillips (1914). The confederation of Europe: a study of the European alliance, 1813–1823, as an

experiment in the international organization of peace. Longmans, Green. pp. 234–50.

For an overview see Wayne S. Vucinich, "Marxian Interpretations of the First Serbian Revolution." Journal of Central

European Affairs (1961) 21#1: 3–14.

Henry Dodwell, The Founder of Modern Egypt: A Study of Muhammad ‘Ali (Cambridge University Press, 1967)

Orlando Figes, Crimea: The Last Crusade (2010); also published as The Crimean War: A History (2010)

"The Long History of Russian Whataboutism". Slate. March 21, 2014.

"The Russian Menace to Europem and the Crimean War - by Marx and Engels 1853-5". www.marxists.org.

See for example: Gladstone, William Ewart (1876). Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East (1 ed.). London: John

Murray.

Sean McMeekin, The Berlin-Baghdad Express: The Ottoman Empire and Germany's Bid for World Power (2012) excerpt

and text search

Erickson, Edward J. (2001). Ordered to Die: A History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War. Westport, CT:

Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-31516-9.

Howard, Michael (2002). The First World War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285362-2.

Wigram, William Ainger (1920). Our Smallest Ally ; Wigram, W[illiam] A[inger] ; A Brief Account of the Assyrian Nation in

the Great War. Introd. by General H.H. Austin. Soc. for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

Zeine N. Zeine (1973) The Emergence of Arab Nationalism (3rd ed.). Delmar, New York: Caravan Books

Inc. ISBN 0882060007. pp. 60–61, 83–92

Yesilyurt, Nuri (2006). "Turning Point of Turkish Arab Relations:A Case Study on the Hijaz Revolt" (PDF). The Turkish

Yearbook. XXXVII: 107–8.

Part II: British and French Strategies

Peter Sluglett, "The Primacy of Oil in Britain's Iraq Policy", in the book "Britain in Iraq: 1914–1932" London: Ithaca

Press, 1976, pp. 103–116

A. J. Barker, The First Iraq War, 1914–1918; Britain's Mesopotamian Campaign (Enigma Books, New York, 2009), 51–54

"The Arab Revolt, 1916–18 – The Ottoman Empire | NZHistory, New Zealand history online". nzhistory.govt.nz.

Retrieved 2021-04-12.

Martin Sicker (2001). The Middle East in the Twentieth Century. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 26. ISBN 978

0275968939. Retrieved July 4, 2016 – via Google Books.

Peter Mansfield, British Empire magazine, Time-Life Books, no 75, p. 2078

Hawes, Director James (21 October 2003). Lawrence of Arabia: The Battle for the Arab World. PBS Home

Video. Interview with Kemal Abu Jaber, former Foreign Minister of Jordan.

Researcher name:

Ally Pitts, Russian Film Podcaster

Lawrence and Oxford

He moved to Oxford with his family aged 8[1] and studied at Jesus College, notable for its links to Wales, where Lawrence had lived as a small child (I’m sure my fellow researchers will go into more detail on his family background). The focus of his studies had mediaeval military history, and he found that there were a great deal of similarities between in terms of organisation, loyalties and logistics between feudal armies and those of the sheiks and emirs in early 20th century Arabia[2].

The Ottoman Empire: Some background

World War I is a historical estuary where the modern and the ancient coincide[3]. On one side of the conflict, the Central Powers, there are two empires that have their origins in the mediaeval period, Austria-Hungary[4], ruled by the Hapsburg dynasty, and the Ottoman Turks.

In 1453, the Ottomans had captured Constantinople from what we call the Byzantine Empire, but who described themselves as “Romans”. Some two and a bit centuries later, the Ottomans had come very close to capturing Vienna from the Hapsburgs in 1683. As these two empires have a common enemy in the Russian Empire, and a common ally in the German Empire, they find themselves on the same team in WWI.

In the intervening period, the Ottoman Empire had been slowly falling apart, and were famously nicknamed “the sick man of Europe” during the 19th century. Initially, the Russian Empire had been the main beneficiary of their decline, but in the 19th century and first decades of the 20th, the Albanians, Greeks, Romanians, Serbs, Bulgarians, and Montenegrins [apologies to any nationalities I’ve inadvertently missed out here] had all achieved independence from the Ottomans as well. Britain had occupied Egypt and the Sinai peninsula[5], and the French had annexed Tunisia.

[1] Anderson p.20

[2] Anderson p.208-209

[3] Pretty sure I’m stealing this idea from Dan Carlin’s Blueprint for Armageddon series, which I have listened to more

times than I can recall

[4] Someone in the German high command may have compared being allied to Austria-Hungary to being “shackled to a

corpse”. Presumably that’s a scenario that’s come up in a Fright Pub movie at some point? Faulkner p. 20

[5] Johnson p. 175

In 1908 a revolution was launched by a group of middle-class army officers calling themselves the Committee of Union and Progress. They demanded the restoration of the short-lived liberal constitution of 1876 which had been proclaimed and then put aside a mere three months later[6]. Though initially motivated by the ideals of the French Revolution and a desire to modernise the empire, the leadership became increasingly autocratic[7].

Following the 1908 revolution, the CUP had operated behind the existing ruling structure of the empire. However, angered by the mismanagement that had led to Ottoman defeat in the First Balkan War (1912-13), they launched a military coup and replaced the previous Grand Vizier, and installed three of their own, Enver Pasha, Talaat Pasha, and Djemal Pasha, as a triumvirate of military dictators.

Ottoman entry into WWI

The Ottomans avoided getting involved at the outbreak of WWI in August 1914, which was sensible, as the casualties in the first months of WWI were orders of magnitude greater than those in the wars of the 19th century. For example, while the French had suffered 270,000 casualties during the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-71, this figure was equalled in less than a month of fighting on the Western Front[8].

The triumvirate wanted to join the war on the German side, but there was opposition among their Cabinet colleagues. However, on 29th October 1914, Ottoman warships commanded by a German admiral acting on secret orders from Enver Pasha, attacked the ports of Odessa and Sevastopol, which were then part of the Russian Empire. The Russians declared war on the Ottomans on 2nd November.

The British massively underestimated the Ottomans, probably in part due to their “sick man of Europe” reputation described above, and proceeded to suffer 350,000 casualties against them in little over a year of fighting on that front, most notoriously at Gallipoli[9].

Ottoman attitude to the Arabs

Khalil Pasha, Ottoman commander of the fortress at Kut in Iraq, claimed that while maybe one in ten Turks might be a coward, only one in a hundred Arabs was brave[10]. Goes to show that making patronising, dismissive, and racist generalisations about one’s imperial subjects wasn’t exclusively a European pastime…

[6] Faulkner p.43

[7] Faulkner p.40-45

[8] Anderson p. 70

[9] Anderson p. 182

[10] Anderson, p. 178

While it’s true that Arab soldiers were more reluctant to press attacks and more likely to surrender than ethnic Turkish soldiers[11], it doesn’t seem to have occurred to Ottoman commanders that being asked to die on behalf of someone else’s empire isn’t exactly motivating.

Following the Arab Revolt, some Turkish officers refused to dine or pray with Arab fellow officers[12].

Religious aspects of the war

German leaders hoped that with the Ottomans on their side, the Muslim subjects of the British and Russian empires might rise up in jihad[13]. Likewise, the British hoped that Sherif Hussein’s religious standing as the custodian of Mecca and Medina could be used to motivate devout Muslims to fight against the Ottomans.

Faisal/Feisal

His father Hussein was made Emir of Mecca and Medina by the Ottoman sultan, apparently to stop the CUP/Young Turks from appointing their own preferred candidate[14]. Unlike his three brothers, Faisal had been educated in Constantinople[15], the Ottoman capital.

Lawrence’s first meeting with Faisal was quite tense, and the latter openly expressed suspicions over British intentions. Lawrence claimed in Seven Pillars of Wisdom, however, “I knew at first glance that this was the man I had come to Arabia to seek, the leader who would bring the Arab Revolt to full glory”. Lawrence also noted that Faisal looked much older than he was i.e. 31[16].

Lawrence was impressed by Faisal’s ability as a manager of relationships; he had a knack for making his subordinates feel listened to and respected[17]. British military leadership in the region, however, favoured Hussein’s eldest son Abdullah[18].

[11] Faulkner p 29-30

[12] Johnson p. 183

[13] Faulkner p. 20-21

[14] Johnson p. 174

[15] Anderson p. 113

[16] Anderson p. 204

[17] Faulkner p.202

[18] Anderson p. 209

The infamous Sykes[19]-Picot Agreement

The secret agreement whereby Britain and France decided how they would divide up the Ottoman Empire once the war was won. Some officials in the governments of the Entente powers described it at the time as “the Great Loot”[20]. These post-war boundaries contradicted what the British had promised to Emir Hussein as an inducement to launch a rebellion against the Ottomans, but Sykes conveniently neglected to mention these promises to Picot[21].

Britain would get parts of Iraq, including Baghdad and Basra, while France would get a large part of present-day Türkiye, most of the Syrian coast, Lebanon, and parts of the Mosul province in northern Iraq. There were also two zones marked A and B that were to be nominally under the control of Arab rulers, but in practice answerable to the French in the case of Zone A, which included inland Syria and central Iraq, and the British in Zone B that included Jordan and the north of the Arabian peninsula The area encompassed by modern Israel was to be run by some kind of international administration, but with Britain expected to take the lead[22].

As the Russians were also a party to the agreement, the Bolsheviks found a copy of the terms when they captured the Winter Palace in St Petersburg during the October Revolution. They published the terms as it fit extremely well with their characterisation of the war as an exercise of imperialistic conquest and enrichment[23]. They themselves would shortly go on to forcibly incorporate as much of the former Tsarist empire as they could into their new, Communist, definitely-not-an-empire-you-can-check-out-any-time-but-never-leave polity.

Historical accuracy of the film

Robert Bolt, the second screenwriter to work on the script said this; “A man’s account of his deeds is already at one remove from the deeds themselves. A second man's evaluation of that account is at another remove again. His dramatisation of that evaluation is at a further remove still.[24]”

The family of Auda abu Tayi, played by Anthony Quinn, unsuccessfully attempted to sue the film’s producers over how he was depicted[25].

[19] Mark Sykes, or to give him his full name, Sir Tatton Benvenuto Mark Sykes, 6th Baronet of Sledmere appears to have

been exactly the sort of upper-class twit of the year that inexplicably large swathes of the English electorate (the other

constituent nations of UK are rather more savvy) still seems to think is well suited to being in charge of things. I’m

being slightly unfair here; he was probably quite intelligent, but his intelligence and lofty social position led him to be

extremely arrogant and sloppy. See Anderson p.153-7 for a detailed description of Sykes.

[20] Anderson p.152

[21] Anderson p. 163

[22] Faulkner p. 259

[23] Anderson p. 404

[24] Patterson p.160

[25] von Tunzelmann

In terms of the film’s portrayal of Lawrence’s ruthlessness, during the retaliation for the Ottoman massacre at Tafas, Lawrence, following a discussion with Auda abu Tayi, who had seen the aftermath of the massacre first-hand, had ordered his subordinates not to take prisoners. In Seven Pillars, he describes himself as saying “the best of you brings me the most Turkish dead”[26].

The screenplay

The first screenwriter was Michael Wilson, who had been on the Blacklist. He quit after having “ideological differences” with Lean and producer Sam Spiegel. The second screenwriter was Robert Bolt, a playwright and history instructor. The latter retained much of the structure of the original script and described Seven Pillars as his “prime, almost [his] only source”[27].

It’s not strictly an adaptation of Seven Pillars of Wisdom, as it draws on other sources too. Seven Pillars of Wisdom is relatively unusual as an adapted text as the subscriber’s abridgement version of the text from 1926 contains illustrations, including portraits, commissioned by Lawrence himself[28], rather than by the publisher, so it’s not a simple case of translating words to images, as the key source text has a visual aspect, and not only that, but those images were selected by the person who is the protagonist of the film.

Some quotes that caught my eye

“In a deeper sense than that of the plot, the background to the story is the Desert. Words cannot trap that landscape. The camera almost can, and did. It is the essence of the saga.” Robert Bolt, the film’s second screenwriter.[29]

This devastatingly scathing description of WWI:

“…at its core this war had many of the trappings of an extended family feud, a chance for Europe’s kings and emperors-many of them related by blood-to act out old grievances and personal slights atop the heaped bodies of their loyal subjects…Europe’s imperial structure had fostered a culture of decrepit military elites-aristocrats and ageing war heroes and palace sycophants-whose sheer incompetence on the battlefield, as well as callousness toward those dying for them was matched only by that of their rivals. Indeed, in looking at the conduct of the war and the almost preternatural idiocy displayed by all the competing powers, perhaps its most remarkable feature is that anyone finally won at all.”[30]

“The Anatolian peasant-conscript - armed with a Rhineland gun, commanded by a Prussian officer, financed by a Berlin bank - was now the hired auxiliary of the German Kaiser. How would he fare in the maelstrom of modern industrialised war into which his leaders were sending him?”[31]

[26] Anderson p. 470

[27] Patterson p. 160

[28] Patterson p. 158-159

[29] quoted in Patterson, p. 167

[30] Anderson, p. 70

[31] Faulkner p. 54

Random Trivia:

A google search threw up that Ralph Fiennes played T.E. Lawrence in a British TV movie from 1990, his first screen role, as far as I can tell.

Ralph Fiennes Lawrence After Arabia introduction

References:

Books:

Indexing an Icon: T E Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom and David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia Alison Patterson in True to the Spirit: Film Adaptation and the Question of Fidelity, edited by Colin MacCabe, Kathleen Murray, and Rick Warner, Oxford University Press, 2011

Lawrence in Arabia, Scott Anderson, Atlantic Books, 2014

Laurence of Arabia’s War Neil Faulkner, Yale University Press, 2016

The Great War and the Middle East, Rob Johnson, Oxford University Press, 2016

Articles:

Lawrence of Arabia: a confabulous romp through the desert | Culture | The Guardian Alex von Tunzelmann

https://www.jesus.ox.ac.uk/about-jesus-college/history/telawrence/

Videos:

Ten Minute History - The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Birth of the Balkans (Short Documentary)

Why Did the Ottoman Empire Join the Central Powers? (Short Animated Documentary)

How the Ottoman Empire was Carved Up (Short Animated Documentary)

When did Constantinople become Istanbul? (Short Animated Documentary)

Podcast/Radio Programme:

BBC Radio 4 - In Our Time, Lawrence of Arabia

One I didn’t get to but looked interesting:

https://uk.bookshop.org/p/books/behind-the-lawrence-legend-the-forgotten-few-who-shaped-the-arab-revolt-philip-walker/1947346?ean=9780198802273

Quotes from Seven Pillars of Wisdom: (available on Audible narrated by Roy McMillan)

“Arabs believe in people, not institutions.”

“Arabs felt no incongruity in bringing God into the weaknesses and appetites of their least creditable causes. He was the most familiar of their words, and indeed, we lost much eloquence when making Him the shortest and ugliest of our monosyllables.”

“The children of Harith are children of battle.” For the first time, the old man’s mouth was full of words.

“After that, Wejh had the silence of fear.”

"TALAL!! TALAAAAL!!”

“By my order we took no prisoners, for the only time in our war.”

“Faisal the profet, and Auda the warrior.”