Mulan (1998): Historical Research (China Focus)

Research by: Michael S. Andrews, Social Studies Teacher, Lummi Nation School

26th October 2023

Introduction

When Mulan arrived in cinemas during the Summer of 1998, it was added to the long line of retellings of a much older story. First thought to have been told, retold, and memorized as a folk song, the earliest written record we have of it is from the 11th century - quite a different China than the one the poem is supposed to take place in. To understand the historical time period that Mulan is supposed to be in, we have to go all the way back to 4th - 6th century China. What was China like back then? Was having a heroine in China something unique? Does the film retain a sense of historical authenticity? Does the film depict Chinese culture, traditions, and values accurately? This research seeks to answer these questions, give the hosts of Danger Close material that is simultaneously well researched, informed, and easy to access during discussion. Please see my references located in the bibliography at the end to learn more.

Thank you,

Michael Andrews

Note: My research is split up into different bulleted points, which are grouped by theme. Spaces in between bullets and bolded titles indicate a change in topic to make my research more organized/easier to find and utilize.

Section I: History of the Ballad

Ballad (400 CE)

- The earliest recorded instance of Mulan is in the Ballad of Mulan. This version is believed to be a folk song.

- It is mentioned as being compiled together by a monk in a book called the Musical Records of Old and New; we only know about this book because of its mentioning by the author of Music Bureau Collection who cites it as a source.

Xu Hwei Version (1593 CE)

- Xu Hwei, a playwright, dramatized the tale as “The Female Mulan” or “The Heroine Mulan Goes to War in her Father’s Place” in 1593.

- In this version, Mulan is given the additional physical trait of foot binding and wonders if she will still be seen as beautiful when she returns after having worn army boots.She worries greatly if she will be married.

- Her parents arrange a marriage for her while she is away, and she apologizes to the husband as she has just returned from war and is “not good enough to be a match”.

Chu Renhuo Version (1500s CE)

- Another famous retelling is in the Romance of Sui and Tang, written as a historical fiction by Chu Renhuo in the 16th century.

- This version highlights Mulan’s virginity, so much so that when given a choice to be the Emperor’s consort or chastity, she chooses chastity and commits suicide over her father’s grave.

Zhang Shaoxian Version (1850 CE)

- The author Zhang Shaoxian reviewed a myriad of retellings and eventually created the novel “Fierce and Filial”.

- The focus is on Mulan’s prowess coming from her strong virtues. The theme of traumatization through military service and cruelty of warfare combines with her refusal to back down from her tenderness and helps her bring the war to an end instead.

- The book still leans heavily on - and accepts - traditional family roles and expectations within Chinese families.

Mulan Joins the Army (1903)

- While still ruled by the Qing Dynasty, a play called “Mulan Joins the Army” began to be performed. Mulan was played by a male opera star, named Mei Langfang.

- Mulan takes over the role of substitute for her father from her cousin Mushu - also a woman - and saves the Chinese commander, driving the Xiongu into a partially frozen sea.

- This is one of the very few examples of a Mulan retelling that does not feature surprise or shock from Mulan’s male compatriots when they find out she is not a man. She still rejects government positions to come back home, however.

Gender Commentary

- According to Shiaman Kua, associate professor of East Asian languages and cultures and comparative literature at Bryn Mawr College, the original ballad is simply about Mulan “getting the job done”. It had less to say about gender revolution and more about the rise of an individual woman in a desperate time, who returns to her prescribed gender role when her emergency need is fulfilled.

Filial Piety

- The Chinese/Confucianism concept of Filial Piety, or proper love and respect for one's family, can help to explain the lack of transgressive gender role-reversal/rejection in the original, non-Western Mulan retellings.

Filial:

1) the old are supported by the younger generation;

2) the young are burdened and oppressed by the old;

3) the purpose of the family is the continuation of the family line

- The idea that Mulan only went to war to serve her father and to happily return to her station as a woman was not completely challenged for over a thousand years. When film and opera began to depict Mulan in a more Nationalistic sense during the Second Sino-Japanese war (1939), more open interpretations of what Mulan was and her motivations took form (see below).

Modern War & Nationalism (1920s-1970s CE)

- A short note on otherwise obscure 1920s silent film versions of Mulan - there were two silent films both taking their story ideas from “Mulan Joins the Army”. Besides not doing very well in China, they chose to depict Mulan as an ethnically Han person rather than a Northern descendent of nomadic peoples (see history section).

- Mulan was a patriotic nationalist icon in this era and fought the Japanese in the 1930s and 40s. Women soldiers dressed as men during the Cultural Revolution, and the opera Who Says Women are not as Good as Men argued for gender equality in China.

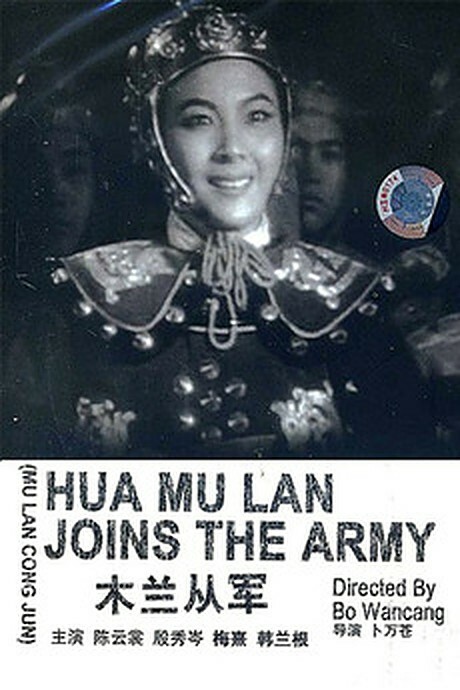

- Another rendition of Mulan Joins the Army released in 1939 and was an instant success commercially and critically in China. She is shown to be far superior to weak-willed and treacherous military commanders on the front. She ends up victorious, and very pro-military, but still resigns at the end and marries her companion after revealing her gender.

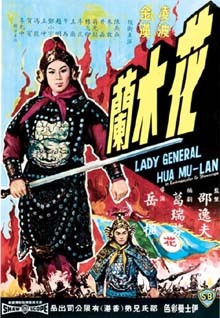

- The early 1960s saw a new Opera come out of Hong Kong - recently reclaimed by the British - and a director named Yueh Feng created a new opera shown on the big screen. Called Lady General Hua Mulan, it was aimed at providing unity among Chinese people in Hong Kong, the Communists, and the Republicans. Rather than focus on pure militarism, it instead promotes a theme of unity.

- Woman Warrior by Maxine Hong Kingston made Mulan recognizable to the Western World in 1976.

The Western Mulan (1998 CE)

- Mulan of the 1998 film follows the trend of 90s Not Like Other Girls rules - meaning, individuality and standing apart from the status quo. As you have seen, this is not really what the original ballad is about nor what it espouses as something to aspire to.

- China did not really care for the Mulan film - not hating it, with one description saying it gave a “sincere effort in understanding Chinese culture”, another described the Mulan character as a “Western lass who grew up eating bread and butter”.

- Originally, in 1993, the genesis of the film was a result of an interest in the original ballad and an idea floating around Disney Feature Animation about a poor, miserable Chinese girl taken back West by a British prince charming character (yikes).

- Luckily, as you will see, Mulan from 1998 attempted to retain some cultural authenticity at the expense of historical authenticity.

- There was no dragon or cricket in the original Ballad - indeed, animal companions were added at the pushing of higher ups like Michael Eisner, to the chagrin of many of the production team.

Section II: China in the 4th - 6th Century

- Despite the dubiousness of the authenticity of Mulan as a real figure, her role as a folk figure is nonetheless important and remains influential internationally today.

- This section seeks to explore the time period the original ballad takes place in rather than tackle all new interpretations and placements of the story. This means exploring the late 4th - 6th century China.

The Northern and Southern Dynasties Period (420 - 589)

- Like many periods of Chinese history, the Northern and Southern Dynasties Period was defined by civil war and flourishing culture, tech advances, and religious spread.

- It arose as a result of the fall of both the Han Dynasty and Three Kingdoms Period.

- Notable inventions during this time period include heavy cavalry standardization (thanks to an earlier development of the stirrup in the Jin Dynasty, 266 - 420), advances in medicine, astronomy, math, and cartography.

- This was the first time in Chinese history that the South became far more prevalent in Chinese affairs than it ever had been. So much so that the following Tang Dynasty shifted the power and focus away from the North to the South.

- The period ended with reunification under the short-lived Sui dynasty, reunifying North and South for some time.

Tuoba & Northern Wei

- The oldest reference of Mulan would have had her as a Tuoba person. The Tuoba have been known by many names, but in Chinese historiography we are told they are named Northern Wei. After the fall of the Han and the Three Kingdoms, the Tuoba ruled a state called Dai in Northern China from 310 - 376, and then restored in 386, renaming the state Wei at this time.

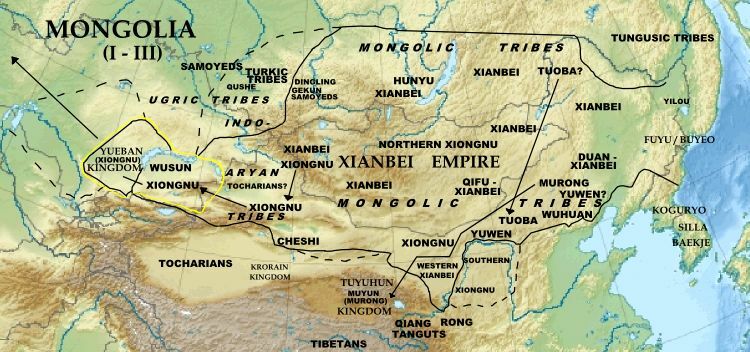

- The Northern Wei have their origins in the Xianbei nomadic people of Mongolia and Northern China. They seem to have been a multi-ethnic confederation of Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic peoples. The Xianbei originate from the Donghu people who were split as a result of defeats at the hands of the Xiongnu in the late Third Century BCE.

- The Northern Wei were incredibly powerful in the Northern part of China, as one might expect. They promoted Buddhism while simultaneously sinicizing themselves. Some of this including marrying exiled or defected Han royalty from the Southern dynasties.

- Sinicizing is the process of an outside ethnic group taking steps to become more culturally Chinese - specifically Han Chinese. We can interpret this process as a legitimizing action among the Tuoba.

- The Emperor of Northern Wei, who ruled between 471 to 499, was known as Emperor Xiaowen, Tuoba Hong, and later Yuan Hong changed the name of the Dynasty from Wei to Yuan.

- The kingdom eventually split between Eastern and Western Wei in 535, with some of the Western Wei’s rulers actually readopting the Tuoba name in 554.

- Because the northern Wei had such extensive contacts with Central Asia, Turkic sources identified the northern Wei as the exclusive “China” well into the 13th century.

Military of the Northern Wei

- The lower classes in the North, the Xianbei, registered as “garrison households”. These were used to garrison the frontiers and not included in formal ranking systems.

- An armor style known as “cord and plaque” became popular. These consisted of double breast plates front and back held together by shoulder straps and waist cords. They used this in conjunction with regular lamellar armor. Figurines depict soldiers of this time holding oval-esque shields and longswords. Light and heavy armor were distinguished during this time as well.

- “Co-fusion” steelmaking was introduced to the North at this time - basically using metals of different carbon contents to create steel. -T he North made use of a tribe called the Erzhu, fighting as “iron-clad” heavily armored cavalry not unlike the cataphracts utilized by Persian, Armenian, and Eastern Roman factions in the West.

The Rouran Khaganate

- The Rouran Khaganate were one of the primary nomadic competitors with Northern Wei. Beginning in 402 when they united, the Rouran Khagante was in perpetual conflict with the Northern Wei - enabling the Rouran to take over parts of the Silk Road and even vassalize the Hephthalites, another powerful Central Asian group famously known as the White Huns.

- Interestingly enough, the Rouran Khaganate are recorded by Chinese historians as having descended from the Proto-Mongolic Xiongnu and Turkic elements.

- Despite this, there are many instances of royal marriage alliances between the two factions (Wei and Rouran).

- In 429, the Northern Wei launched a major offensive and we are left with the following comments on military strategy against the nomadic factions to the north:

“The Chinese are foot soldiers and we are horsemen. What can a herd of colts and heifers do against tigers or a pack of wolves? As for the Rouran, they graze in the north during the summer; in autumn, they come south and in winter raid our frontiers. We have only to attack them in summer in their pasture lands. At that time their horses are useless: the stallions are busy with the fillies, and the mares with their foals. If we but come upon them there and cut them off from their grazing and their water, within a few days they will be either taken or destroyed.”

Emperor Daowu of Northern Wei

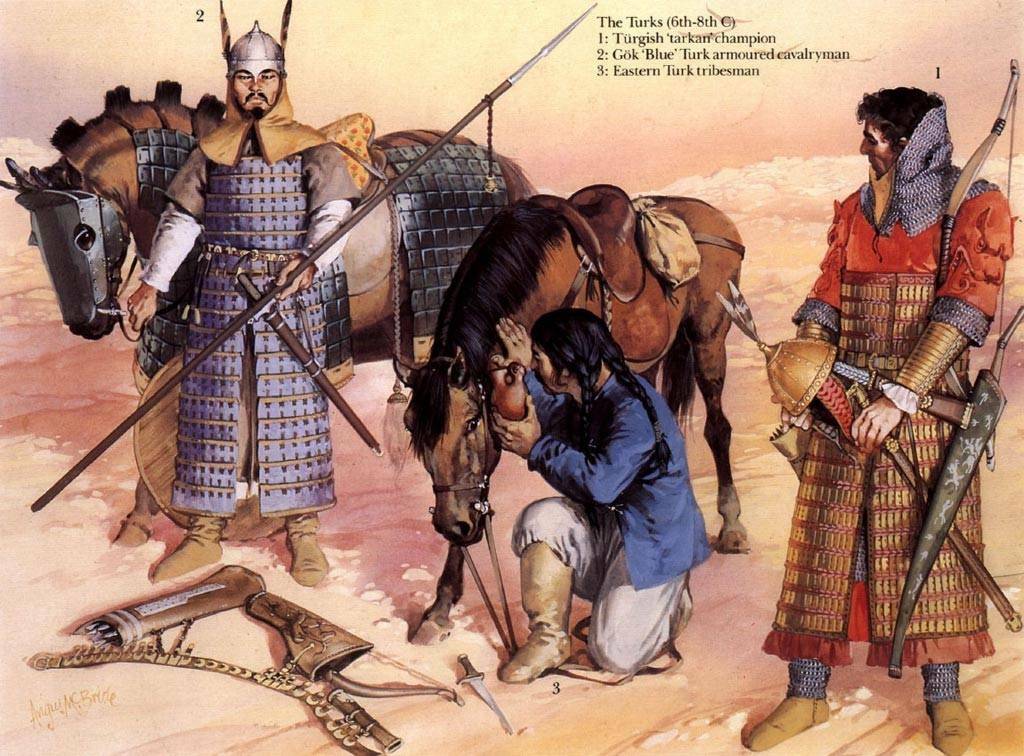

- In 492, the Emperor Tuoba Hong apparently sent 70,000 horsemen in an expedition against the Rouran. Chinese sources do not say what the outcome of this expedition was as it was likely unsuccessful. -Between the years 525 - 527, Rouran soldiers were employed to help put down some of the many uprisings that took place in Northern Wei, leading to local plundering and violence against the populations. -In 555, Turkic peoples laid waste to Rouran land and anyone who escaped was later handed over to the Turks and killed if over the age of 16. The Tatars and Avars may be descendents of the Rouran Khaganate. -The take-away is the Rouran Khaganate and the Northern Wei relationship ebbed and flowed between mortal enemies and dubious allies. -The Khaganate is described as a militarized society that sought to specifically requisition products from neighboring nations and states through whatever means necessary. -Nomadic confederations typically utilized cavalry-centric armies to devastating effect against sedentary societies. It is probable the Khaganate used tactics and equipment not dissimilar from neighboring Turkic peoples (see figures below).

The Northern Wei and the Great Wall

- The Northern Wei, because of their quest to better legitimize themselves as Chinese, became far more dependent on agriculture than their nomadic ancestors. This led them to use defenses that were more passive than they were used to.

- The Great Wall of China was (and is) less a contiguous unended fully defended wall and more a network of smaller sections periodically manned during different dynastic periods. The Wei built 2,000 li (670 miles) of wall that would help prevent attacks by the Rouran Khaganate in 423.

- In 446, 100,000 laborers built an inner wall that helped protect the capital of Pingcheng.

- Both of the aforementioned double wall segments would later protect Beijing during the Ming Dynasty 1,000 years later.

- Aside from the Great Wall additions or restructuring, the Wei established the Six Frontier Towns to stave off Rouran invasions. These towns later rebelled in 528 against the Wei, requiring the Rouran to bring them back into line!

Section III: A Critique of the Film’s Depiction of Chinese History and Culture

Liberties with the Ballad

- Disney’s Mulan has to take liberties with the original poem to help create a different kind of character. Chinese gender roles are depicted so strictly in the film that Mulan’s revolution is far more impactful.

- Instead of facing a capital crime for cross-dressing in the film, the original ballad has a more lax view (ironically) when Mulan reveals she is actually a woman. The soldiers seem to be more “Oh no! Anyways…” because they know she is going to return to her prescribed gender role now that her duty to her father is over.

- Even in the more Western-style characterization of Mulan, the film still puts Mulan happily back in her gender role to some degree. It creates a bit of dissonance as she is given a stricter version of China with a more independent spirit, and yet still ends up in a similar place.

Historical Time Period

- It is important to remember that Mulan is a folklore hero, and not a historical one. Although there have been and are attempts to prove some kind of solid historical connection.

- The film takes place in a significantly different era of Chinese history than in the ballad. It chooses to center around the Xiongu conflict with the Han Dynasty, hundreds of years before the ballad takes place (late 2nd century CE).

Chinese Culture

- Many significant cultural details are depicted somewhat authentically throughout the film with some glaring exceptions.

- The opening of the film uses the most prominent style of art and writing in Chinese history - ink brush painting.

- The Great Wall should feature flags with the Dynasty in charge rather than dragons. This is forgivable because the Ballad of Mulan exists within several different dynasties and retellings, and the filmmakers seem to have taken a royal symbol like the dragon and ran with it.

- Many men in the movie wear their hair in knots, or “man-buns”. Every part of your body was considered a gift from your parents in Confucian thinking. This meant if you cut it, it was disgraceful and also damaging to your family’s property.

- The use of signal fires to communicate military messages is accurate. These were called Langyan, or Wolf Smoke (because wolf or other animal dung was mixed with sulfur and saltpeter.

- If you have made it this far, the line “Now all of China knows you’re here” does not make sense historically. But, many changes we see in the movie are done to cater to Western audiences who might not be familiar with Chinese history (the word “China” comes from the West, most likely from the Qin dynasty). Instead of China, the dynasty name would make more sense.

- The Huns are a familiar name, but whether they are made as the Huns or the Xiongnu, they should be the Rouran Khaganate. The Huns are far more recognizable, however, than either.

- The idea that the Emperor could and would call a levee or conscription is accurate, as many dynasties utilized non-professional military forces for combat or labor. Dynasties risked the wrath of their conscripts when called upon too frequently or used poorly by the state.

- A small but comical detail is Mulan puts her chopsticks in her rice vertically, sticking out of the food in the bowl. This was a major offensive problem because it resembles incense sticks sticking up and burning for the dead, so Mulan doing this is basically cursing anyone around her to die!

- Mulan’s ancestral shrine is bafflingly outside the family complex (which is otherwise quite accurate). Also, the dragon as their family symbol is unlikely as that was reserved for the imperial family. One of the reasons that the shrine has the tombstones inside and not an altar to place food for the ancestors is because the production crew went to China and saw people kneeled in front of gravestones. It’s an example of not going quite far enough to achieve cultural authenticity by consulting with people in-country but instead observing and utilizing.

- The word honor is a bit overused - a term like “saving face” might be more appropriate for Chinese culture and expectations. Western popular culture’s views of most Asian cultures over-emphasizes honor as a term.

- Rickshaws, palanquins and horses are being used for transport, all fairly accurate modes of transportation.

- Although it is accurate for women to be riding horses to town in this era, it is more likely all of Mulan’s aunties and the matchmaker would go to their house because of how well off her family is.

- The makeup is fairly accurate in the film, however the eye shadow should be more of a peachy color.

- The conscription notice being brought to the town by a tower drum is accurate as these would have been staples in Chinese townships.

- Dragons were less like lizards or crocodiles and more like snakes in Chinese mythology. Also, they spit water rather than fire!

- The Emperor being captured and held hostage in his own palace has occurred multiple times in Chinese history!

- Peak Asian family representation - Mulan’s father hugs her for all that she has done, but her grandmother is upset she did not bring a boyfriend home.

Conclusion - My Commentary on the Research

Overall, the Mulan retelling of 1998 gets major Chinese cultural aspects correct without being historically accurate or very authentic. The changes made reflect a desire to make the film acceptable for a wide range of human beings, including a Chinese audience and, especially, a Western audience.

As you can see from the many interpretations of Mulan, each new retelling fits into its era, adapting the ballad as the author sees fit with the perspective of the time period they live in. From folk hero, to Cultural Revolutionary, to pro-Militarist, to the great uniter, to strong independent woman, it seems that Mulan is malleable enough within and without Chinese culture to be used as a creator sees fit.

That being said, Mulan does a great job at introducing ignorant viewers to a semblance of Chinese history and culture, and my own study and rewatching of the film has made me learn way more about Chinese history than in any recent memory. It also made me appreciate the depth and complexity of Chinese history - and the wide range of cultures, militaries, strategies, and politics that entails.

I hope this research proved useful for you, and I look forward to listening to the episode!

Michael Andrews

Appendix I: Figures

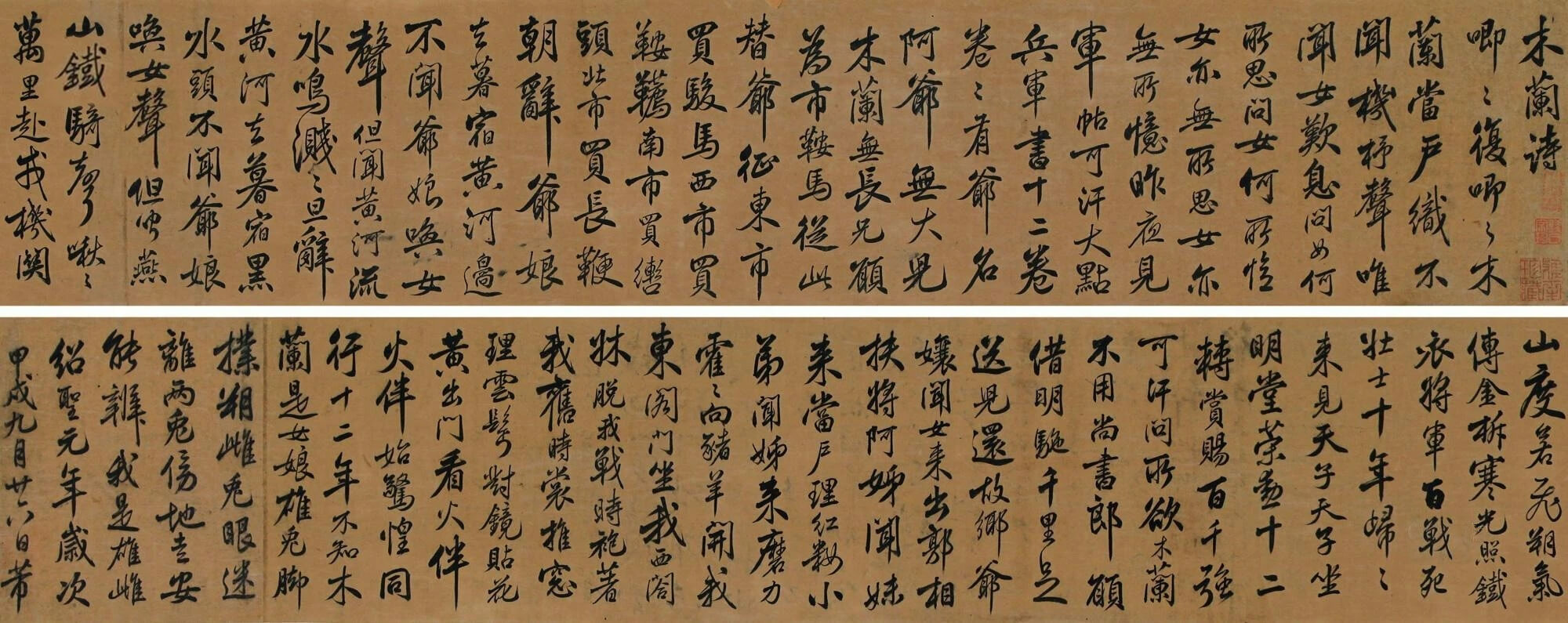

Figure 1. This copy of the Ballad was penned by Song dynasty calligrapher Mi Fu in 1094 AD (Public domain).

Figure 2. Mulan Joins the Army (1939) Poster.

Figure 3. Lady General Hua Mulan (1964) Poster. Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9466527

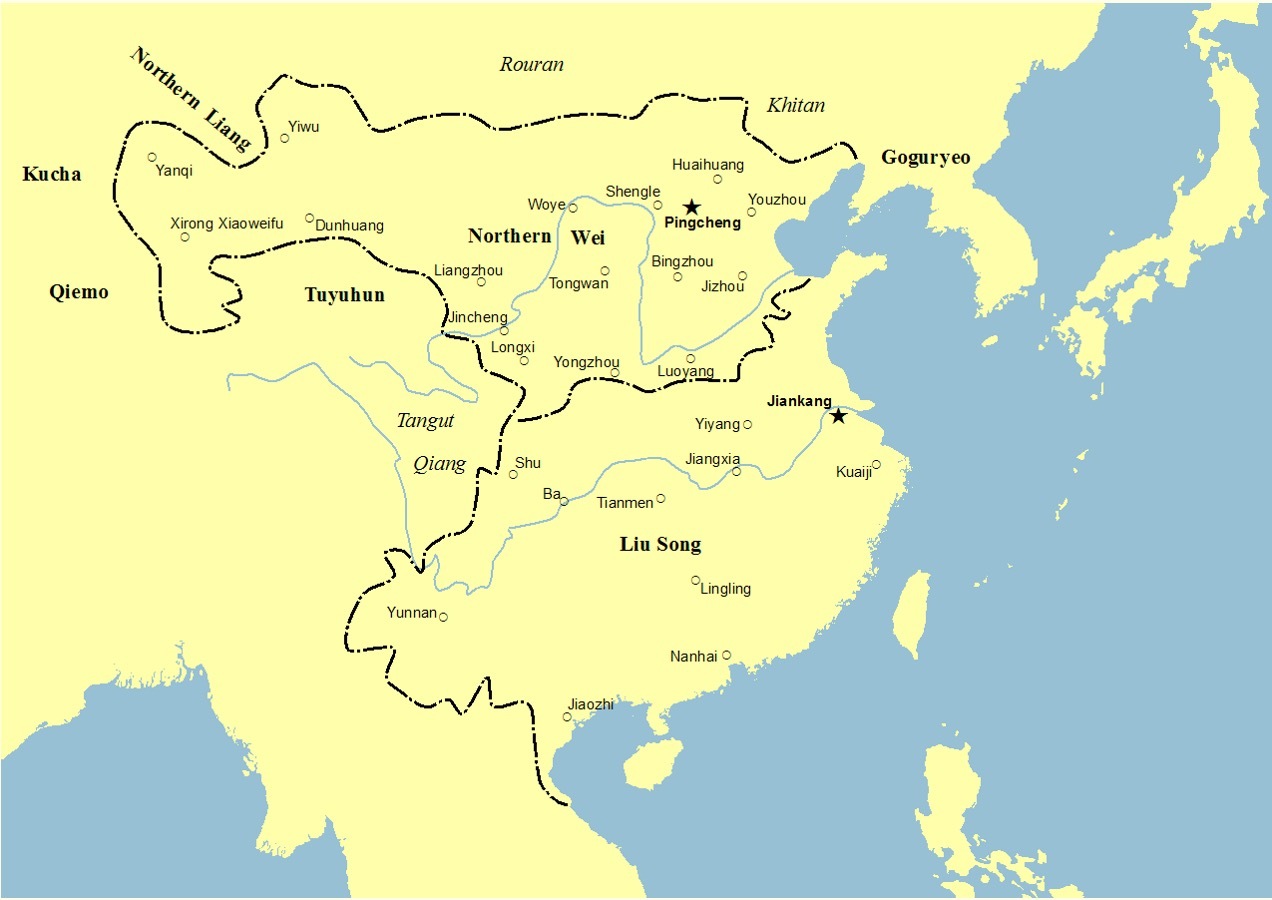

Figure 4. Northern and Southern Dynasties circa 497: Northern Wei and Southern Qi

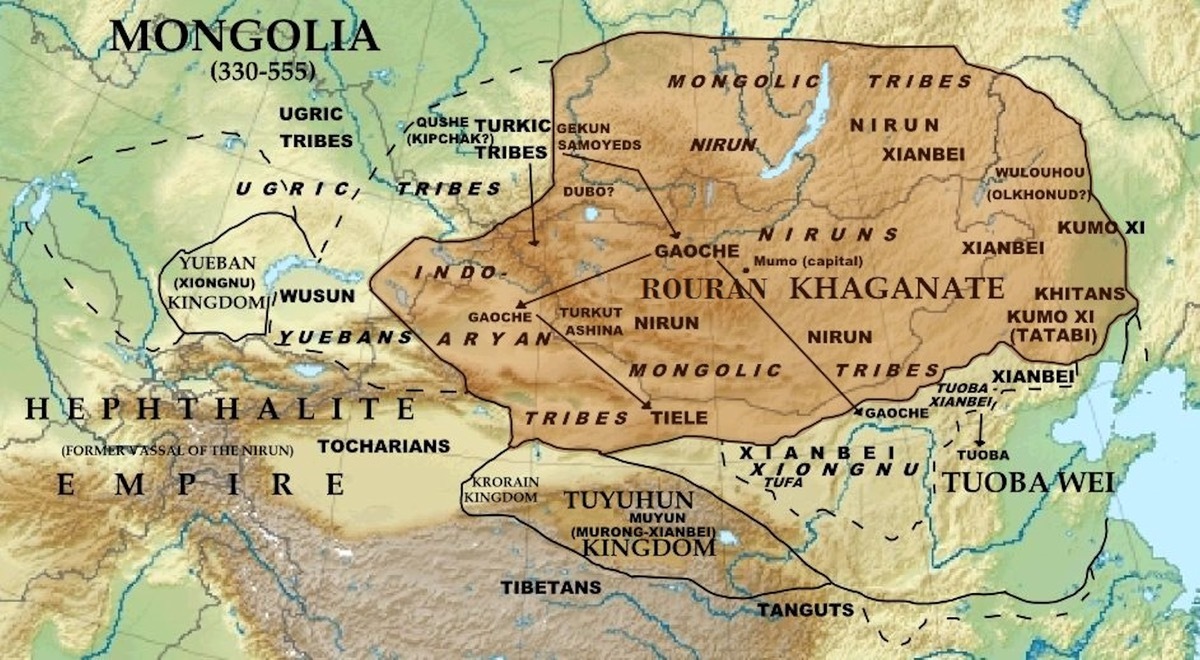

Figure 5. Core territories of the Rouran Khaganate in Eastern Asia.

Figure 6. Northern dynasties shieldbearer.

Figure 7. Northern Wei cavalry.

Figure 8. Examples of Turkic horsemen - not too dissimilar from what the Rouran Khaganate would field.

Bibliography

Section I

Grady, Constance. “The History of Mulan, from a 6th-Century Ballad to the Live-Action Disney Movie.” Vox, 4 Sept. 2020, www.vox.com/culture/21412785/mulan-history-original-chinese-ballad-disney.

Haynes, Suyin. “Is Mulan Based on a True Story? Here’s the Real History.” Time, Time, 11 Sept. 2020, time.com/5881064/mulan-real-history/.

Holzwarth, Larry. “The Real Legend of Hua Mulan.” History Collection, 6 May 2022, historycollection.com/the-real-legend-of-hua-mulan/10/.

Huang, Martin W. (2006), Negotiating Masculinities in Late Imperial China, University of Hawaii Press, pp. 67–68, ISBN 0-8248-2896-8

Kwa, Shiamin; Idema, Wilt L. (2010), Mulan: Five Versions of a Classic Chinese Legend with Related Texts, Hackett Publishing, ISBN 978-1-60384-871-8

“Filial Piety (孝) in Chinese Culture.” The Greater China Journal, 23 May 2023, china-journal.org/2016/03/14/filial-piety-in-chinese-culture/.

“The History behind the Legend of Hua Mulan (400 AD Onward).” The Legend of Hua Mulan: 1,500 Years of History, mulanbook.com/pages/overview/history-of-legend-of-mulan.

Section II

Biran, Michal (2005), The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World, Cambridge University Press. p. 98.

Gascoigne, Bamber (2003). The dynasties of China : a history (1st Carroll & Graf ed.). New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 978-0786712199.

Graff, David A. (2001), Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300-900, Routledge, p. 99.

Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 60–61, 67. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

Kradin NN (2005). "From Tribal Confederation to Empire: The Evolution of the Rouran Society". Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 58 (2): 1–21 (149–169).

Kurbanov, A. The Hephthalites: Archaeological and historical analysis. PhD dissertation, Free University, Berlin, 2010

Lewis, Mark Edward (2009). China between Empires: The Northern and Southern Dynasties. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02605-6. p. 130-135.

Lovell, Julia (2006). The Great Wall : China against the world 1000 BC – 2000 AD. Sydney: Picador Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-330-42241-3.

Pearce, Scott (2019). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 2, The Six Dynasties, 220–589. Cambridge University Press. p. 179.

Peers, C.J. (2006), Soldiers of the Dragon: Chinese Armies 1500 BC - AD 1840, Osprey Publishing Ltd. p. 94, 99.

Wagner, Donald B. (2008), Science and Civilization in China Volume 5-11: Ferrous Metallurgy, Cambridge University Press. p. 256.

Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2009), Historical Dictionary of Medieval China, United States of America: Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 978-0810860537

Xu Elina-Qian, Historical Development of the Pre-Dynastic Khitan, University of Helsinki, 2005. pp. 179–180

“The Turkic Khaganate.” Daily Scribbling, 16 May 2014, dailyscribbling.com/forgotten-empires/the-turkic-khaganate/.

Section III

Note: Sources mentioned above were used for the following section as well, in addition to the video below:

Xiran Jay Zhao. (2020, October 4). EVERYTHING CULTURALLY RIGHT AND WRONG WITH MULAN 1998 [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8SHC7CnmErM

So Hard They Never Sang: the Huns/ Xiongnu in "Mulan"

by Dave Feldmann

Swords, armor, beating people up with blunt and/or sharp objects.

Note: Throughout and wherever possible, I will be noting the culture, language, and if possible the ethnicity of individuals involved. While the steppe people the Han Chinese derisively referred to as “Xiongnu” were made up of predominantly Altaic, Tokarian, and Iranian-speaking peoples, and their mostly Han counterparts in Imperial China speaking Mandarin, there is in fact a great deal of mixing between them throughout their long exchange of people, ideas, trade, religion, and warfare. Many steppe people of various languages and cultures served the Han emperor, and likewise, many Han Chinese defected to the Xiongnu, although their memories are now reviled as traitors (漢奸) by Chinese historians. The court eunuch Zhonghang Yue (中行說) who served as a tutor to Chinese princess given to the Xiongnu as part of the tribute system, is just one example.

In 1998’s Mulan, we have our vaguely ancient Imperial Chinese heroine Mulan fight against the villainous Shan Yu and his army of Huns in their attempt to capture or kill the good Emperor and either rule or destroy China. They are portrayed as horse-riding arsonists wearing vaguely Mongolian clothing, being physically larger than our Chinese heroes, breaching the Great Wall with little effort, and defeating whole Imperial armies easily albeit off-screen. In short they’re scary. These Huns are not portrayed as loafs, idiots, or subhuman for the most part (their yellow with black irises notwithstanding) which is a refreshing change after reading Roman and Chinese translations regarding the steppe peoples. The Huns are only outwitted by our far-cleverer-than-most heroine Mulan, with their leader Shan Yu ultimately meeting his end through the power of friendship.

In reality, the Huns never fought the Chinese Emperors, only the Roman ones. When the movie was released to audiences, the bad guys were called “Huns” for Western audiences and “Xiongnu” for Chinese audiences. While this is probably because no one knows in the West who the Xiongnu were and they probably know who the Huns or Attila were, Disney is knowingly and ignorantly engaging in some pseudohistory for western audiences. At worst, it’s a deliberate and prejudiced overgeneralization about steppe peoples with the only justification being that Western audiences are too stupid to understand the difference. Unfortunately, they have almost three hundred years of well-intentioned but mistaken Western scholarship and perhaps at least 2300 years of inaccurate historical inquiry to back them up. This may seem like a history buff’s pedantry, but the sad truth is that misconceptions, overgeneralizations, and questions of identity, especially with regards to the former steppe peoples, have in the past led to distrust, prejudice, and wars of genocide. As I write this, such a genocide has been underway since 2014 in the western Chinese province of Xinjiang, its target the Turkic-speaking people the Uyghers, complete with “re-education” concentration camps to destroy traditional Uygher culture and government-sanctioned sexual assault.

But first, the history.

We’re hamstrung here because by and large, steppe people don’t write down their histories, The Secret History of the Mongols and the plethora of literature written at the direction of Timur the Lame being obvious exceptions. What we do have is a lot of works written about them by their enemies, which can fill volumes. While I recommend that everyone dig in and read as much as you can stomach about Attila and the Huns, we have to look at the Xiongnu instead because that’s who the bad guys of Mulan actually are.

At the end of the Warring States period in the third century BCE, the Qin emperor, Qin Shi Huang ( 秦始皇,) defeated his enemies and united China. We saw this portrayed in the Jet Li movie Hero and (if you believe the Chinese Communist Party) more polemically in The Emperor and the Assassin. Qin Shi Huang ruled a united China as its first emperor or huangdi (a title he bestowed on himself), and under his authoritarian leadership went about consolidating the many kingdoms and peoples under his rule into a single imperial entity. Steppe peoples of various tribes, cultures, and ethnicities had been plaguing the frontier for years, with the disparate Chinese states setting up various forts and defenses over the years. Shi Huang saw these defenses and fortifications and turned them into a combined centralized effort which in later centuries become the Great Wall. This earlier version was not the long masonry snaking on mountains viewed by modern tourists but rather a ditch and tower fortification, with vulnerable passes walled but certainly not contiguous across northern China. It is thought that various military expeditions sent by the Qin emperor fortified a particular area as quickly as possible and then moved onto the next troubled area. These fortifications were apparently never intended to be a border, like at Hadrian’s wall, but rather a fortress which would be readily available should the steppe nomads from the north invade.

While the fortifications were built as at least a temporary defense, Shi Huang also directed his general Meng Tian to begin operations against the Xiongnu in the loop of the Yellow River, on the Ordos plateau. Despite the Xiongnu having withstood the various attempts of different Chinese incursions over the years, this one was successful. Meng Tian’s forces defeated the Xiongnu and expelled them from the Ordos in 215 BCE.

It is not known how many of the Xiongnu were living in the Ordos region at the time, but Meng Tian’s campaign was decisive and traumatic. No doubt that during the course of the campaign many of the Xiongnu’s military leaders were killed or captured and their armies severely mauled. They did what steppe peoples have always done after a catastrophic defeat by Imperial forces- they ran. Or rather, they rode. In Chinese sources, the Xiongnu’s chanyu (vocally similar to the villain of “Mulan” Shan Yu) retained power and fled north to the plains and grass fields of modern day Mongolia. Within a few years of the defeat in Ordos, this same leader and his tribe were pestering China again, and doing it from the Ordos.

Before we go on, we have to answer the question: who were these Xiongnu?

Short answer, we don’t know and we most likely will never know. The “Xiongnu” (匈奴) did not call themselves that, their Chinese enemies did and have been calling this iteration of the steppe confederations of the eastern steppes “Xiongnu” ever since. It does not take very much investigation into the history of Chinese dealings with the Xiongnu to understand that official history holds the people, customs, language and culture of the steppe people in deep disdain. Translating the Mandarin word “Xiongnu” into English can fluctuate between “fierce slave” and “illegitimate offspring of slaves.” Some sources claim that these people called themselves “Xia” or “Hu,” but both of these names are Mandarin Chinese, and the steppe peoples of the north had different languages than that of China. Indeed, when Chinese sources refer to “Hu,” it should not be understood as a specific term for a specific people but rather a generalized term for steppe peoples in the eastern steppes surrounding China on two sides. By the best and most recent studies on the subject, the people the Chinese called the Xiongnu were most definitely a mix of Turkic and possibly Iranian-speaking peoples. Whatever the actual meaning of their name, the Xiongnu in northern China had been in some kind of tribal confederation, and after the defeat at Ordos each tribe went their own way.

This was probably the intention all along. As is evident from sources going back to the invention of writing, steppe peoples had always been a danger to settled peoples, their skill with horses granting them a maneuverability advantage that settled peoples simply couldn’t match. But many writers of the centuries have discussed the differing means to minimize this threat as much as possible. Money and trade were certainly tools to buy off steppe raiders -- life on the steppe was difficult even in the best of times. Diplomacy and marriage were other tools, used successfully for generations to play one steppe tribe against the other. The one thing to be avoided at all costs was the building of a tribal confederation under a single ruler or powerful council. Throughout all the ages that they have existed, the political structure of steppe confederations did not have the strength of continuity enjoyed by their settled compatriots. I am of the opinion that such a confederation existed in Ordos plateau, and that political, rather than social, entity, was Shi Hunag and Meng Tian’s target.

Unfortunately for them, neither Shi Hunag nor Meng Tian lived long to enjoy their success, nor did the Qin dynasty. After years of assisination attempts, Shi Hunag’s paranoia grew into an obsession with immortality, and amongst the many the many attempts to forestall the inevitable, Shi Huang’s doctors concocted a life-giving serum that held dangerous amounts of mercury. He died in 210 BCE. Meng Tian, perhaps the most celebrated general of the Qin dynasty, ran afoul of the new Qin ruler and was executed. The Qin dynasty did not last much longer, and was replaced by the Han dynasty which lasted into the third century CE.

The chaos of the fall of the Qin dynasty gave the Xiongnu some breathing space, and under the remarkable leader Modu Chanyu, (Chanyu being the name at the time for high king or emperor among the steppe peoples - as well as sounding like the name of Mulan’s villain), numerous steppe tribes were conquered and brought under the first imperial steppe confederation. The frontier region of the Ordos plateau and the modern day province of Xinjiang were also conquered. Modu Chanyu defeated the Han emperor in battle and exacted tributes from them in return for peace. Small scale raiding continued but was frequently used by Modu Chanyu to exact better terms from the Han emperors.

Modu Chanyu’s new empire was based upon the foundation of tribute from the Han emperors. Many Han princesses were sent to Modu Chanyu’s stronghold in modern day Mongolia. (not far from where Genghis Khan would have his court near Karakorum) as part of the extended peace treaty, along with silks, jewelry, and other booty. These treasures were then distributed to the heads of other tribes in order to bind them closer to the imperial throne of the Chanyu. Over the years, Modu Chanyu also attracted many Mandarins from the Han court and instituted a formal bureaucracy to oversee the empire -- it should be noted that no such administration ever existed in a steppe confederacy up to that time.

The arrangement was continued by Modu Chanyu’s successors, lasting for nearly a hundred years until the Han emperor Wu decided that the ever-increasing tribute to the Xiongnu should cease and traded peace for unceasing and total war. Emperor Wu put the Han empire on a permanent war footing and trained cavalry for the first time, launching his attack in 129 BCE. The Han emperors’ forces outnumbered the Xiongnu field armies many times over and defeated them in decisive battles, but the Xiongnu as almost exclusively horsemen retained their advantages in mobility and evaded destruction in detail. After each defeat, the Xiongnu would retreat across the Gobi desert or into the Mongolian steppe, where the Han forces could not follow. Though the Xiongnu lost control over the Ordos plateau and the province of Xinjiang, the end of the tribute system weakened the power of the Chanyu’s grip over the confederation.

The war would go on for centuries, interrupted occasionally by truces. The expense of maintaining operations nearly bankrupted successive Han emperors, and hundred of thousands of Han soldiers were killed in battle, died of disease, or starvation in steppes. In one campaign only ten thousand survivors out of an army of a hundred thousand returned to Han territory in 104 BCE.

For the Xiongnu, the war took on genocidal proportions. Losing the rich grasslands of northern China, forced the Xiongnu to live in starker regions. Han records indicate that in each yearly campaign Xiongnu foodstuffs and livestock were captured or destroyed. The strain caused the confederacy’s political structure to weaken further, and ultimately the Xiongnu’s imperial structure ended in a civil war, breaking apart in 60 BCE. The northern kingdom would ultimately be defeated in 155 CE. The southern kingdom would persist however into the third century, and though the confederacy would split into smaller kingdoms, they remained a power in the land. A Xiongnu prince would one day assume the throne of China, and found the Han - Zhou dynasty in 304 CE. Tribal steppe confederations would continue to plague China’s emperors into the modern age.

The concept that the Huns and the Xiongnu were in fact the same people has a centuries long tradition. First suggested by the French Orientalist, Sinologist, and Turkologis Joseph de Guignes in his 1756 work Histoire générale des Huns, des Mongoles, des Turcs et des autres Tartares occidentaux, de Guignes suggested that the Huns and the Xiongnu were the same same people separated by the distance and the languages of the people they terrorized. Put simply, the Xiongnu achieved dominance over China when it was broken up into warring states, but when the Ching and Han dynasties rose in power, they threw out the Xiongnu - Huns in the 3rd century CE. Recovering for a century, and.still hungry for conquest, the Xiongnu - Huns rode across the steppe in the 370s and set up in the Caucasus, Ukraine, and the Hungarian plain. In the process, their aptitude for war and terror drove the Goths (these guys not these guys) into at first seeking entrance into, and failing that, making war on the Roman Empire in the 370s. The thesis was persuasive enough Edward Gibbons used it in his monumental “The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” as the origin of the Huns. Unfortunately, while the Xiongnu and Huns appear to be culturally distinct from one another, the origin of the Huns remains shrouded in a historical mystery unlikely to ever be solved. The fact that “Hu,” the Mandarin word for Steppe people, and the historical arsonists known as “the Huns” share some obvious similarities in their respective names, is enough for the pseudohistory to persist.

However, in his book Empires of the Steppes, Kenneth W Harl of Tulane points out that beyond the long historiography of this connection, there is precious little evidence to suggest that the Huns and the Xiongnu were actually the same people. While neither the Huns nor the Xiongnu never left anything comparable to the written records that Rome and Han China were each founded on, archaeological evidence from both the Huns and the Xiongnu are clearly at the very least culturally different.

This Hun - Xiongnu connection has become so pervasive in the understanding of the trials and tribulations of the Roman Empire in the West and its Han dynasty counterpart in the east that this grad thesis was written back in 2020 discussing just such a historical connection.

Maps

From Tuoba People and their neighbors

From https://www.worldatlas.com/geography/xiongnu-empire.html

An example of the strong Ferghana horses ridden by the Xiongnu and prized by the Han emperors https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferghana_horse

More artifacts can be viewed here.

Special thanks to listener David Wang who provided a transcript to the translation of The Ballad of Fa Mulan