Dr. Patrick Conner

PhD in medieval english & literature, 31+ years teaching British literature

Notes on Approximate timelines in The Vikings (1958)

The Viking is based on the 1951 novel The Viking by Edson Marshall (A quick summary/review of the novel can be found here: http://www.historicalnovels.info/Viking.html).

The novel draws on material from the Norse sagas of Ragnar Lodbrok, whose life was both historic as well as driven by Scandinavian legend and folklore. His sons led a Viking invasion of East Anglia in 865 according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and other medieval sources. Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus in his late 12th century Gesta Danorum tells us also that Ragnar was a 9th-century Danish king whose campaigns included a battle with the Holy Roman emperor Charlemagne. According to Saxo’s legendary history, Ragnar was eventually captured by King Aella of Northumbria and thrown into pit of snakes to die. This story is also recounted in the later Icelandic works Ragnars saga loðbrókar and Þáttr af Ragnarssonum.

The 12th-century Icelandic poem Krákumál provides a romanticized description of Ragnar’s death and links him in marriage with a daughter of Sigfried and Brunhild, figures derived from ancient Germanic legend.

The historic materials of the screenplay then are obliged to adhere to the ninth century while other items would seem to belong to other times, such as the love affair between the novel’s invented characters, Ogier and the Welsh princess, whose story approaches the conventions of courtly love which we do not much find in Scandinavia, certainly not the Scandinavia of the ninth or 10th centuries.

Archaeology has given us a great deal more information today about Scandinavian, British, Roman, and Anglo-Saxon dress, ceremonial buildings, and ceremonies themselves than the 1950s offered us. On the other hand, we might expect to see as much of ninth century Germania portrayed in The Vikings as we would see of any other culture which mythologizes itself in its own time long before it’s captured in cinema.

It requires somebody with a knowledge of medieval material culture to look at the film and say whether it reasonably matches the time I’ll give you: CE 825. -ish. If you saw Mel Gibson‘s Hamlet, you saw images from the Book of Kells, Lindisfarne Gospels and similar Gospel books and their wonderful Celtic designs on the walls of the castle in Denmark. Many critics loved this. This was so wrong, I almost couldn’t stomach it. Gospel illustrations, whether you give a personal damn about the Christian gospels or not, were never ever intended by anybody to be wall paintings in a secular castle. I bring that up, because there may well be instances of things that belong more or less to the time here but are wrenched out of place. But I don’t know any examples from the film. (Tell me there are no horned helmets.)

Ragnar was the son of the king of Sweden, Sigurd Hring, who I think died around 804, and Ragnar took his place. Sagas tell us he had several sons at the time. The Anglo-Saxon chronicle seems to be naming him at a raid on Northumbria in 865. Not long after that, he seems to have been captured and killed. I think that’s in my earlier statement somewhere. Look for snake pits. Depending on the age of his sons in 804, he was around 25 when he took his father’s place on the throne. Surely he could not have gone to war in Northumbria at 80 some years of age in 865. So I would extrapolate that we should see him in the film as being no older than about 40 years old at most and that would put him around 825 or thereabouts. That’s my guess. It’s nothing but a guess.

The problem is that there are many tales told about the men in the oldest sagas, but the sagas just tell the tale. They rarely date the time. Now the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, in all of the manuscripts of the Chronicle, take a great deal of care to add the dates at the beginning of each short description of the year. That’s because there’s a lot more Roman heritage in what they are doing and, it follows, Christian concerns with how long Christ has been gone and when he’ll come back than the Norse were interested in. They preserved amazing genealogical records, but they don’t date things. So if you mention 825 or thereabouts as a good year for these happenings, please don’t suggest it’s a learned conclusion because it isn’t.

Dave Feldmann

Undergrad and unofficial medievalist, current practitioner of Historical European Martial Arts.

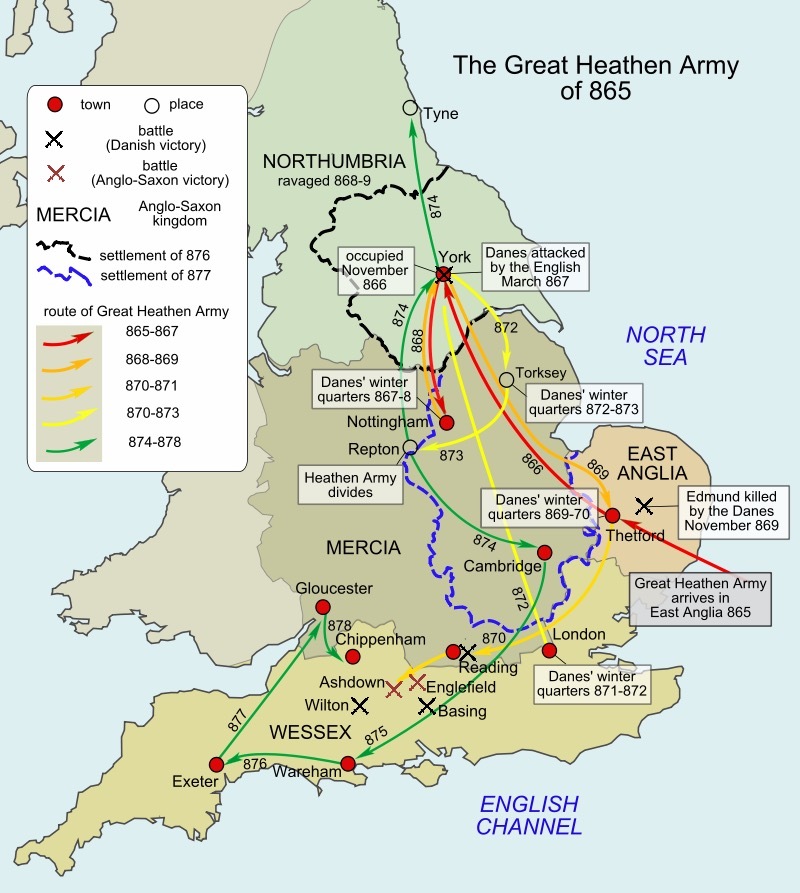

So building on what the other guys wrote, we can definitively say that the movie "The Vikings" most likely takes place in 865 give or take a few yew years. According to the later sagas (written in the 10th through 12th centuries), Ragnar Lothbrok's death at the hands of the Anglo-Saxon Northumbrians was the inciting incident for a large invasion of England known as "the Great Heathen Army." The big castle assault at the close of the film more or less could be called a depiction of the Viking's attack on the Northumbrian city of York, which was captured in 866 according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a legal record which provides contemporary evidence for the period. Interestingly, the Chronicle does not provide any information as to the cause of the invasion, or any involvement by Ragnar Lothbrok's sons (represented by Einar in the movie, played by Kirk Douglas). The sons of Ragnar Lothbrok, including historical figures like Ivar the Boneless and Ubbe, are documented historical figures even if their relationship to the Ragnar Lothbrok is most likely a later invention from the Sagas. Ragnar himself is a historical figure who appears in many sagas and contemporary sources, most of which conflict with one another. The sagas cannot even agree on whether or not Ragnar Lothbrok is from Norway, Sweden, or Denmark. The best way to describe Ragnar is that he is a legendary figure -- Ragnar lived and did stuff, but it's difficult to sift truth from fiction given all the evidence associated with him.

There were four Anglo-Saxon kingdoms at the time, Northumbria in the North, East Anglia, Mercia, and Wessex. Since the raids had begun nearly a century before, Anglo-Saxon leaders both fought and paid off Viking raids in the past, payments being referred to as "danegeld", and attempted to do so with the Great Heathen Army on multiple occasions -- Alfred the Great, king of Wessex, used both strategies before he defeated the Vikings at Edington in 878. By that time, Wessex was the only kingdom left to the Anglo -Saxons, but the Great Heathen Army had been decisively defeated and its final leader, Guthrum, converted to Christianity and departed Wessex. England was divided in two between the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms (ultimately Wessex and Mercia) and the so-called Danelaw, East Anglia and Northumbria, where Danish or Norse leaders would hold power. It should be noted that in Danelaw regions, a merging of Saxon and Norse culture seems to have been in evidence in architecture, dress, coinage and other physical cultures (thanks here to Samantha Rose, who is currently studying for a grad degree on Viking physical culture in Scotland). Settlers from Scandinavia are also in evidence, especially throughout the regions under the Danelaw.

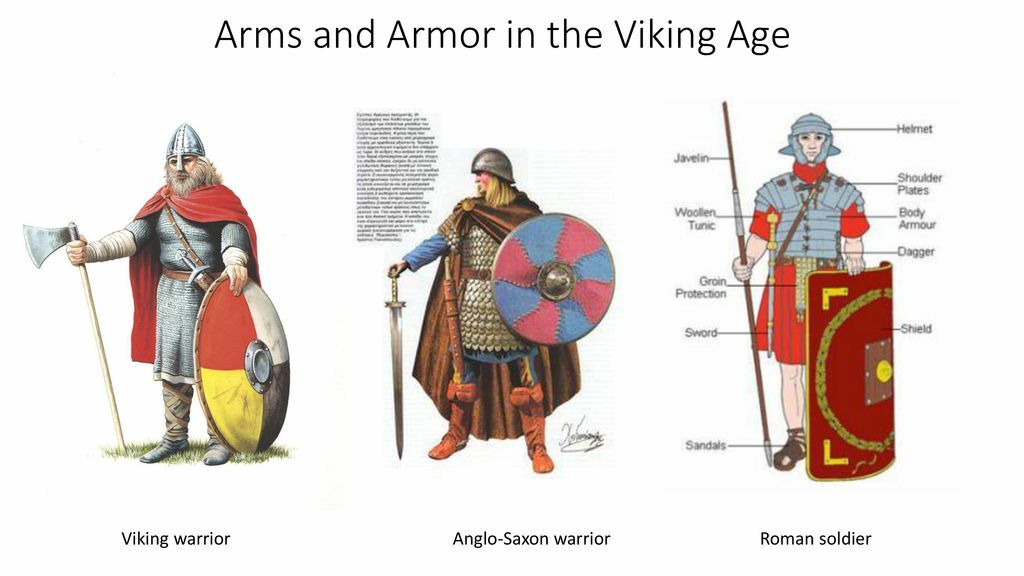

Kirk Douglas, who played Einar in the film was reported to have focused on gritty reality, but in terms of physical culture, it looks very much like a costume-shop barbarian costume. According to grave finds, the clothing worn by the Vikings in the film is pretty inaccurate. Scandinavian culture at the time was what's called a visual status society that placed high value on colorful dress with the Rus of Sweden in particular were known for wearing yellow. Red clothes required dyes that needed to be traded for outside Scandinavia, and were associated with high status individuals or royalty. Grave finds within the Danelaw are typically made of spun wool and linen, rather than the fur and darkly colored garments depicted in the film.

As we discussed a few days ago, the term "Vikings" is kind of a catch-all term applied to Scandinavian raiders of the time, and is very much an obsession among non-Scandinavian peoples. In Old Norse and current Icelandic, the word "Vik" simply means "bay," as in protected body of water. Scandinavian towns were typically built in a bay, so "Vikings" literally means "bay-dweller." For Icelandic people I've spoken to on the subject, the term "townies" is used, presumably because the people who typically would be interested in raiding or profitable voyages of discovery could typically be found among the poorer or landless people living in towns and trading stations throughout Scandinavia. What's also interesting is that North American colonists would be for the most part drawn from the same class of urban landless poor centuries later.

Regarding the fighting in the film, it's pretty inaccurate although fun. As discussed in the "Kingdom of Heaven" notes, any sword combat of the period would have used a shield and tried to stab the opponent rather than the cut and slash, saber-style fighting we see in the movie. Swords themselves were not in great supply -- a typical Viking raiding party would have more axes and spears per soldier with swords carried by wealthier or noble individuals. The other reason why the hack-and-slash stuff is wrong is that this style is a good way to actually break your sword, especially if the sword was not made properly. (This has happened to me in tournaments before, badly made swords will snap after a few heavy cuts).

What is also interesting is how the Vikings in the film are portrayed as better at fighting than the Anglo-Saxons. In the prologue, Ragnar overcomes a Saxon king without much difficulty, and the Vikings defeat the Saxons pretty quickly once they're inside the walls. Contemporary sources do describe Viking raiders as particularly fierce in battle, but the descriptions are very similar to how Roman sources described Alemanni, Frankish, or Gothic barbarians centuries before, and there are theories that scribes were essentially copy and pasting from earlier sources and applying it to their own work.

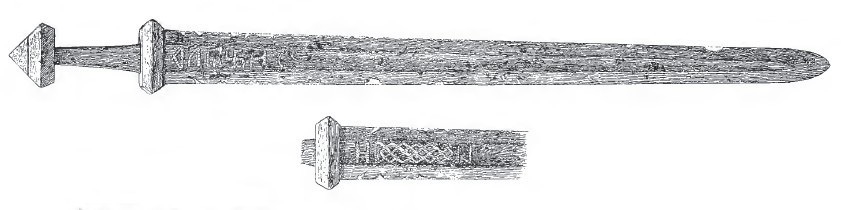

A Viking era sword from the Derby museum in the UK. It is 3 feet long, which implies a user of about six feet tall. Dilly stones in Scotland are associated with Norse culture, and are traditionally thought to indicate that if you could lift a Dilly stone, you could serve on a ship. Most older stones are 250 to 300 pounds, so given these two data points, you have a picture of a large statured man for the time period, which coincides with grave finds as well. Here contemporary records and modern archeology support one another: in addition to being fierce in battle, Viking raiders are also described as being tall and physically stronger than their opponents. There are many explanations for this ranging from diet to pseudoscience, but thats a whole different story -- regardless, in the movie, the Vikings are depicted as being big, strong, and healthy, and this they got right.

Also, many of the graves of Viking warriors have been revealed to be females and shieldmaidens -- this recent interpretation is supported both by archeology and the sagas themselves. Shieldmaidens are all over modern media associated with the Vikings, and are completely absent from the 1958 film.

This is a drawing of the Sæbø sword, found in a Norwegian barrow and thought to be from the early 9th century, slightly earlier than the Great Heathen army.

The Vikings were in fact pagans, following the old Germanic Pantheon with Odin, Thor, Tyr, Loki and others. Thor in particular seems to have been more common and popular -- Dan Carlin did a whole episode on this with "Thor's Angels."Most Scandinavian settlers would ultimately convert to Christianity over the centuries of the Viking Age, and is generally regarded as one of the reasons why the raids and invasions ultimately ended - by the 11th century, Christian lords and kings would often give Viking leaders lands for themselves instead of cash payments or danegeld. This is the origin of Normandy, which would conquer England in 1066 and found the Plantagenet dynasty.

Mike DeAngelo posted in our FB group post-episode publishing:

England existed for 139 years before 1066.

Angle-land had existed for a while as the section of Britain ruled by the Anglo-Saxons, but England as a unified state was first envisioned by Alfred the Great of Wessex. The unification of England would occur in 927. It was united by Æthelstan, grandson of Alfred the Great.

In 1016 England was in personal union with Denmark and Norway under Cnut the Great. After Cnut's death England passed to Harold Harefoot then Harthacnut, before coming back to the House of Wessex with King Edward the Confessor in 1042.

Upon Edward the Confessor's death in 1066, Harold Godwinson became king. Harald Hardrada challenged Harold Godwinson but was killed at the Battle of Stamford Bridge. That is considered the end of the Viking age.

Harold Godwinson lost the throne to William the Bastard of Normandy in 1066, forever ending Anglo-Saxon rule of England.

One of the super interesting bits of history is that as raiding became more difficult, the Vikings actually sold their services as mercenaries. Notably they became the Varangian Guards, the elite force and bodyguard to the Roman Emperor in Constantinople.

After the defeat at Hastings, the English housecarls became refugees. Eventually they became the Varangian Guards. Meanwhile the Normans that had defeated them would fight against the Byzantines in Southern Italy. So they would face the Normans again.