Dennis Meyers

Relevant experience: U.S. Army, 1974-1980, BA & MA Economics, Economist for over 30 years for State of California, Community College Adjunct Faculty

Gettysburg chronicles the pivotal Civil War battle.

Who was Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain?

Col. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain was complex and historically important person—a scholar, a man of letters and languages, a wartime leader and hero, and a popular governor. The movie focuses on his most famous achievement—the defense of Little Round Top. There is, however, a great deal more to this remarkable person.

Outside of Civil War historians and aficionados, Joshua Chamberlain was one of the least well-known Civil War heroes until a series of popular media catapulted his prominence. He is now one of the best-known Civil War figures due to a popular books and documentaries including Michael Shaara's novel The Killer Angels (1975), Ken Burns's PBS documentary miniseries The Civil War (1990), the movie Gettysburg (1993), and the TV miniseries Gettysburg (1993-94). The place where his 20th Maine fought at Little Round Top is the most visited site at Gettysburg National Military Park.

In the movie Gettysburg, the story of Chamberlain ends with the defeat of Lee. However, Chamberlain went on to become one of the most remarkable soldiers of the Civil War and after the war he became one of Maine’s most revered figures; dubbed "The Grand Old Man of Maine".

Chamberlain was born into a family with a multi-generational military history intertwined with U.S. history. [It is interesting that in the movie a recitation of historical connections only appears for the Confederate side.] His great-grandfather Ebenezer was a New Hampshire soldier in the French and Indian and the Revolutionary wars. His grandfather, Joshua, was a colonel during the War of 1812 and his father served as a lieutenant-colonel in the 1838-39 Aroostook War (a confrontation between the U.S. and the U.K. over the boundary between the British colony of New Brunswick and the U.S. state of Maine).

Chamberlain was born in Brewer, Maine, on September 8, 1828. His father, Joshua Chamberlain, urged him to follow a military career. His first name at birth was Lawerance, named after U.S Navy Captain James Lawrence, famous for ordering “Don't give up the ship. Fight her till she sinks" in the War of 1812. Conversely, his mother, Sarah Dupee (née Brastow), wanted him to become a clergyman. Chamberlain taught himself Greek so he could be admitted to Bowdoin College in 1848 where he studied theology and foreign languages. He graduated in 1852 and then earned a Bachelor of Divinity from Bangor Theological Seminary, where he studied in Latin and German and mastered French, Arabic, Hebrew and Syriac (a variant of Aramaic).

Chamberlain became an abolitionist while at Bowdoin. “Slavery and freedom cannot live together" he once said. While at Bowden he met the abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe while she was in the process of writing Uncle Tom’s Cabin. He attended gatherings where Stowe read excerpts the novel in process which moved him to believe in the abolitionist cause.

In 1861 Chamberlain became professor of modern languages at Bowdoin. But he considered it his duty to fight and despite entreaties and enticements from the college, including a two- year sabbatical in Europe, to keep him from signing up, in August 1862 Chamberlain went to the state capital and was appointed Lieutenant Colonel of the newly raised 20th Maine regiment.

After being mustered into service on August 29, 1862, The 20th Maine was engaged in some of the most fierce and significant battles of the Civil War, beginning with the Battle of Fredericksburg December 11–15, 1862—after which Chamberlain was promoted to Col. and given command of the 20th following the transfer of its initial commander Col. Adelbert Ames.

The 20th’s defense of Little Round Top at the Battle of Gettysburg, July 1–3, 1863, is depicted in the movie and earned Chamberlain the nickname "Lion of the Round Top." Long after the war, for this action, in 1893, he received the Medal of Honor.

After Gettysburg it fought in the Battle of Cold Harbor, May 31 to June 12, 1864 followed by the Second Battle of Petersburg, June 15–18, 1864. While leading an assault on Confederate trenches he was shot through both hips. Assuming the wound to be mortal, Ulysses S. Grant promoted Chamberlain to brigadier general on the field--one of only two such occasions in the war--so he could die at that rank. In spite of predictions, he recovered and returned to lead his brigade - and eventually a division - in the final campaign of the war, the Appomattox Campaign; March 29 – April 9, 1865. However, this wound would cause him almost constant pain for the rest of his life.

At the Battle of White Oak Road (also known as the Battle of Quaker Road, Military Road, or Gravelly Road) on March 29, 1865, he received another wound in the left arm and chest that almost caused an amputation and earned him the nickname "Bloody Chamberlain." He continued to lead his troops in several more fights during the next eleven days until the surrender at Appomattox. He was brevetted to major general by President Lincoln. [brevetted: given a higher rank title as a reward for gallantry or meritorious conduct but not with the authority or pay of real rank.]

Following Lee’s formal surrender at Appomattox Courthouse, Chamberlain was chosen to preside over the parade of the Confederate infantry as part of their formal surrender. Legend has it that Chamberlain ordered his men to come to attention and "carry arms" as a show of respect. [Some questions have been raised about the accuracy of this action because Chamberlain’s memoirs are the main account of it.]

Throughout the war, Chamberlain served in 20 battles, was cited for bravery four times, had six horses shot from under him, and was wounded six times.

After the war Chamberlain was not content to be a professor again. After a stint as acting president of Bowdoin in 1865-66, he accepted the Republican nomination for governor. He was elected in 1866 by a landslide and reelected three more times, twice by the largest margin in the state's history. His victory in 1866 set the record for the most votes and the highest percentage for any Maine governor by that time. He would break his own record in 1868.

He left politics to serve as Bowdoin’s president from 1871 through 1883. During his tenure, he attempted to modernize its curriculum by adding courses in science and engineering, social sciences, and modern languages. This innovation was opposed by some alumni and trustees who didn’t want to secularize Bowdoin. His innovations were ended in 1881. In 1883 Chamberlain resigned, largely due to pain and debilitation from a flare-up of his Petersburg wound.

After leaving Bowdoin, he practiced law, served as Surveyor of the Port of and was involved in a variety of business ventures such a Florida real estate, electric power, a New York art college, hotels, and railroad projects.

Chamberlain also supported veterans’ organization and projects to commemorate the war. He lectured on war subjects, wrote scores of articles and one book—The Passing of the Armies—his Civil War memoirs (published one year after his death).

Chamberlain died of his lingering wartime wounds in 1914.

Interesting Facts:

Chamberlain and the Battle of Gettysburg were referenced in Steve Earle's song "Dixieland" from his 1999 album The Mountain.

I am Kilrain and I'm a fightin' man

And I come from County Clare

And the brits would hang me for a fenian

So I took me leave of there

And I crossed the ocean in the "Arrianne"

The vilest tub afloat

And the captain's brother was a railroad man and he met us at the boat

So I joined up with the 20th Maine

Like I said my friend I'm a fighting man

And we're marchin' south in the pouring rain

And we're all goin' down to dixieland

I am Kilrain of the 20th Maine

And we fight for Chamberlain

'Cause he stood right with us

When the johnnies came like a banshee on the wind

When the smoke cleared out of Gettysburg many a mother wept

For many a good boy died there, sure

And the air smelted just like death

I am Kilrain of the 20th Maine

And I'd march to hell and back again

For colonel Joshua Chamberlain

We're all goin' down to dixieland

I am Kilrain of the 20th Maine

And I damn all gentlemen

Whose only worth is their father's name

And the sweat of a workin' man

Well we come from the farms

And the city streets and a hundred foreign lands

And we spilled our blood in the battle's heat

Now we're all Americans

I am Kilrain of the 20th Maine

And I'd march to hell and back again

For colonel Joshua Chamberlain

We're all goin' down to dixieland

From the album The Mountain released in 1999.

Sources:

The Grand Old Man of Maine: Selected Letters of Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, 1865-1914. United States, University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain. National Park Service.

https://www.nps.gov/people/joshua-chamberlain.htm?utm_source=pocket_mylist

Medal of Honor Monday: Army Maj. Gen. Joshua Chamberlain. U.S. Department of Defense

https://www.defense.gov/Explore/Features/Story/Article/2086560/medal-of-honor-monday-army-maj-gen-joshua-chamberlain/utm_source/pocket_mylist/

Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain. American Battlefield Trust.

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/joshua-lawrence-chamberlain

Wikipedia articles: Joshua Chamberlain, Aroostook War, 20th Maine Infantry Regiment

Dave Feldmann

Explaining the significance of the Battle of Gettysburg is a mammoth task, given that tens of millions of words have been written about it. Historian James McPherson, who considers it the most important event in the Western hemisphere, reported that Soviet historians considered Gettysburg to be as important to American history as Stalingrad was to the Soviets(1). For southern historian and novelist Shelby Foote, the epic defeat of the Army of Northern Virginia required Biblical allusion - the chapter about Gettysburg is entitled “Stars in their Courses,” as if all things, natural and supernatural, went against Robert E Lee and the Confederates in the war’s largest battle(2). Michael Shaara, in his influential novel the Killer Angels, directly connects the first onset of Robert E Lee’s ultimately fatal heart problems with his thinking and mentality leading up to and during the battle.

(1) https://www.c-span.org/video/?177242-1/hallowed-ground-walk-gettysburg#

(2) Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative. Fredericksburg to Meridian,p 428. Randam House, 1963.

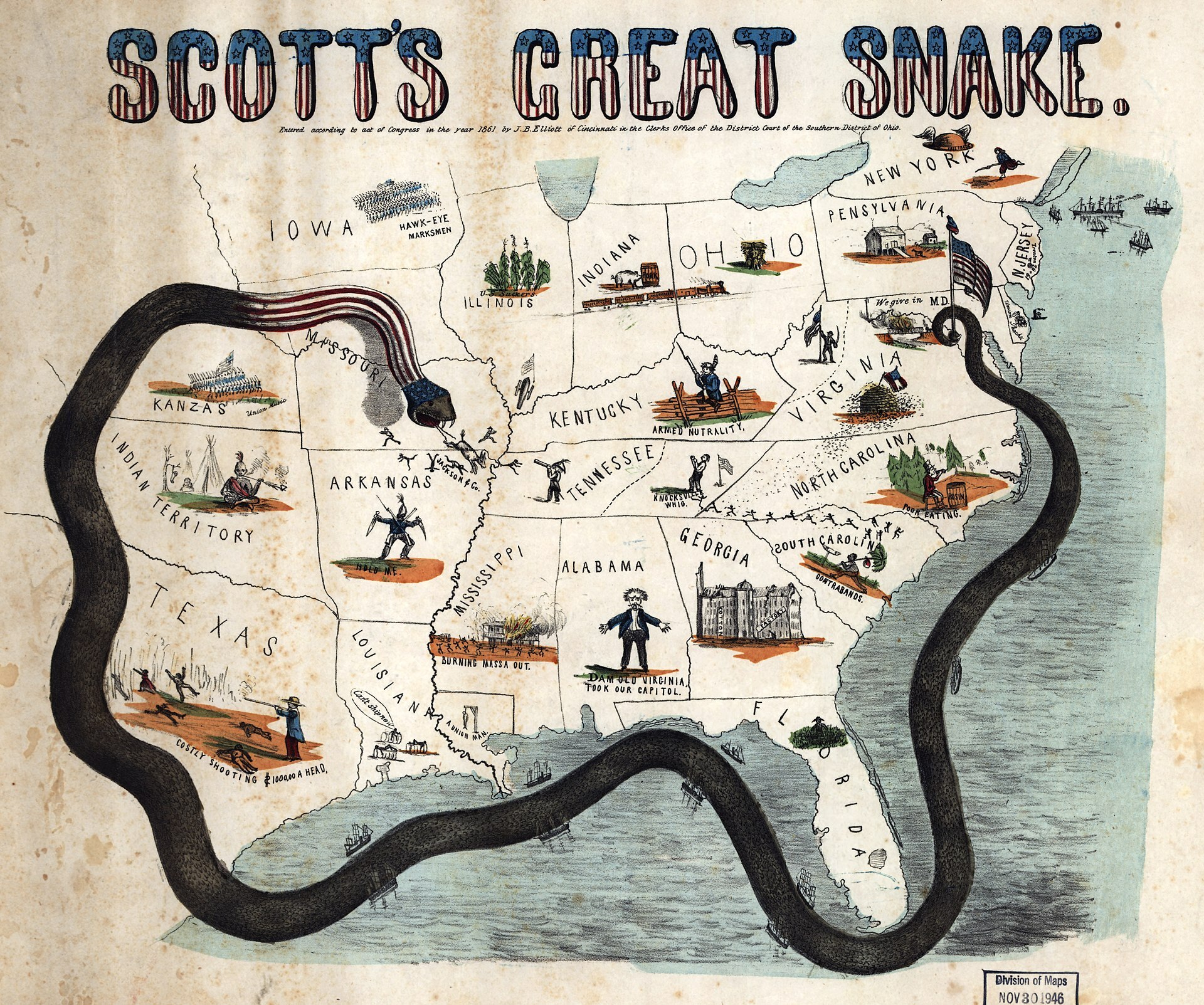

It would be logical to note that at the time of the showdown in Pennsylvania, the Confederacy was running on as much borrowed time as Lee’s diseased heart muscles. General Winfield Scott’s Anaconda plan, which saw the US navy blockade Southern ports, while Union armies picked off Confederate armies and whole states, was wreaking havoc on the Confederacy’s war-fighting abilities.

At the secession in 1861, most economic activity in the South was exclusively focused on export cotton, with a highly stratified social hierarchy, between rich planters (many of whom were represented in Confederate military and civilian leadership), a large class of poor, typically renting, whites, and, obviously, the approximately 4 million slaves that made up almost 40% of the Southern population, produced almost all of its wealth, was the cause of secession and the Civil War itself, and whose experience was and is largely ignored by pro-South and Lost Cause-oriented historians.

It should also be noted that financially, the South was never likely to stand on its own for long. The prevalence of the slavery-based cotton and agricultural economy had slowed or stopped the development of urban centers and industry, depriving the Confederacy of a diversified, modern economy. Deprived of its main export, the CSA had little other means to support itself, and thus the South was in the midst of an economic collapse, with debt instruments issued in rapidly deflating “grayback” Confederate dollars. On the political side, the strong state governments that voted for secession rarely gave heed to their own chief executive, Jefferson Davis, and regularly denied the Confederate government even the small taxes raised for the war effort. Needless to say, the land and slaves that caused the Civil War ironically could not be monetized into war material, unless of course the white supremacist, albeit desperate, Confederate leaders offered freedom to slaves fighting for the Confederacy. When this was considered in early 1865, Confederate politician and general Howel Cobb wrote, “If slaves will make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong.”(3)

While Gettysburg raged, the far more strategically significant siege of Vicksburg, Mississippi continued to progress in the Union’s favor. The vaunted “Gibraltar of the West” ultimately surrendered on July 4th,1863 to Ulysses S Grant after a month-and-a-half long siege. Not satisfied with the naval blockade of Southern ports, essentially halting the Southern export oriented economy, the Union had now disrupted the internal trade system of the South. Union gunboats now controlled the entire Mississippi river from New Orleans northwards, and Union generals Grant and Sherman had cloven the Confederacy in two. There would be guerilla wars against partisans and bandits west of the Mississippi river, but all major Confederate operations would be conducted in the increasingly small theater of Georgia, the Carolinas, the Virginias, and, briefly, in the state of Tennessee. Gettysburg’s contribution to this strategic narrative is that the war would indeed go on as it had for the last two years - Union advances in the West, and a bloody stalemate in the lands between Washington DC and Richmond, VA.

But wait, why aren’t you talking about all of the incredible battles that Robert E Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia fought against overwhelming odds from 1862 to 1863? Isn’t he the greatest military commander of all time? I wrote a Quora article on this subject which covers my thoughts pretty well on this long-debated historical point, and I don’t think I need to go into it too deeply here, except to say that Lee’s bloody clashes with the Union Army of the Potomac were as devastating to his own cause as it was to his adversary.(4) Whereas the Union reinforced itself and went on the offensive time and time again throughout 1862 - 1863, the resources that the Confederacy could count were dwindling fast. For the Confederacy, the second invasion of the North was a desperate gamble to destroy the Army of the Potomac once and for all, to threaten or actually capture Washington DC, and at the very least, allow the devastated state of Virginia to catch its breath. Arguably, the most important goal was not military at all, however. Lee envisioned, and CSA President Jefferson Davis agreed, that the goal of an aggressive action in the North may empower the Democratic peace wing to force a negotiated settlement on Lincoln and the Unionists. Davis and Lee both believed that such a diplomatic coup, perhaps even with international recognition of the CSA (still withheld) by European powers, would be the only path to victory. According to Foote, Lee even made the case that a victory in Pennsylvania might even relieve the siege of Vicksburg in Mississippi. Wherever possible, peaceful treatment of Northern civilians, with food and provisions purchased in Confederate graybacks rather than being “requisitioned” as the Union army did in the South, might sway Northern public opinion towards peace. Needless to say, the Army of Northern Virginia was less than successful in all of these endeavors.

(3) https://jubiloemancipationcentury.wordpress.com/2015/01/28/if-slaves-will-make-good-soldiers-our-whole-theory-of-slavery-is-wrong-confederate-howell-cobb-on-black-enlistment/

(4) https://www.quora.com/What-made-Robert-E-Lee-such-an-effective-general-Why-did-he-succeed-for-so-long-with-the-odds-stacked-against-him?top_ans=105165566

Take the first objective of the second invasion of the North, what would ultimately be called the Gettysburg campaign: the destruction of the Army of the Potomac, in a decisive battle like its ancient counterparts in Cannae, Gaugamela, or more recently at Waterloo. This is the strategy of Alexander, Frederick the Great, Napoleon, and the influential French military thinker Antoine Jomini: aggressively engage the enemy, bring superior forces to bear on a single point of the enemy’s line, and destroy them in detail. Lee and the early, undeniably outstanding military leaders of the Army of Northern Virginia, had very nearly accomplished this many times against their Northern opponents -- the Seven Days Battles, the second battle of Manassas, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville had all been massive engagements, each one roughly equal in size and scope to the largest Napoleonic battles half a century before, as well as being larger and bloodier than the more recent Crimean war fought between European powers. In each of these engagements, the Army of Northern Virginia had committed itself completely in aggressive and bloody attacks on the Union lines, with each battle ending in a Union withdrawal. In the recent battle of Chancellorsville, just a few weeks before Gettysburg, the Confederates had driven elements of the Army of the Potomac in chaotic, disorderly, wild retreat, including the Union XI Corps, which during the battle of Gettysburg would again be attacked, outflanked, break in disorder. However, in each of these battles, the Union army would hold a significant manpower advantage, and keep significant forces in reserve. Whole divisions, sometimes whole army corps, would not fire a shot in anger during these bloody affairs. As such, even when defeated and in disarray, the Army of the Potomac could use fresh, unengaged troops as a shield behind which their beaten army could reforge itself. Despite winning tactical victories, Lee and the Confederates never destroyed the Army of the Potomac. To attempt to do so in Pennsylvania, after the South’s greatest victory at Chancellorsville, proved too tantalizing a target for Robert E Lee.

The next objective, to assault or capture the capital of Washington DC, would prove an even greater challenge for the Confederates. Siege assaults like the one in Vicksburg were simply beyond the limited material means that was a fact of life for Confederate armies. Supplying the army in Virginia was a difficult enough process, with basic necessities like boots and extra clothes being relative luxuries for the poor whites who made up the soldiers of the Confederacy. Supply and reinforcement was simply impossible on the northern side of the Potomac for the Confederates, and such menial logistical concerns are even now prerequisites for successful sieges.

Making matters worse, even were the Army of the Potomac destroyed in detail in Pennsylvania, the Confederates would still had to deal with the roughly 40,000 garrison troops in fortified positions around Washington. Assaults against such fortified positions were typically the war’s bloodiest, and were very much the precursors of the trench warfare that would dominate the Western Front of World War One. At Fredericksburg, at Gettysburg with Pickett’s charge, at Cold Harbor the following year, it would be proven, tragically, time and time again, that a Civil War rifleman could not prevail against his counterpart in a pit or trench, armed with a rifled musket and supported by artillery. Confederate general James Longstreet was one of the few men on either side who understood the incredible, exponential disparity in power between the offensive and defensive capabilities of Civil War armies. His revolutionary theories on infantry tactics, intended to minimize casualties, would most often be ignored by both sides.

It must also be pointed out that the moment it was clear that the Army of Northern Virginia had in fact crossed into Pennsylvania, militia units were called out almost immediately; far-disbursed across the state certainly, but numbering some 50,000 guardsmen. A number of these militiamen successfully burned the longest covered bridge in the world at Wrightsville, Pennsylvania, denying its use to the Confederates and preventing General Early’s division from attacking the railroad hub at Harrisburg upriver. While it is doubtful that such militia units would prove themselves the equal of the battle-hardened Confederates in a set-piece battle, during a siege they might prove a harmful distraction, just as their Southern counterparts proved time and time again during the more numerous operations against the Union.

The goal of providing an opportunity for Virginia to be spared more fighting was achieved if for little more than a few weeks. After the battle the Army of the Potomac once again invaded Virginia, and operated on Confederate soil relatively unimpeded by the still diminished Confederate army.

Perhaps the greatest failure of the invasion was in its ability to divide the North via the peace movement, active among Democratic circles in the North, and force a negotiated settlement. While the lack of violence to white citizens north of the Mason Dixon was undoubtedly welcome, the Confederates’ attempt to purchase goods from northern stores was less well received than Robert E Lee hoped, according to Foote and others. The more commercially-minded Pennsylvanians knew that the Confederate greyback was worth less than the paper it was printed on, and could not be exchanged for any good or service as such. While peaceful, Confederate requisitions in Pennsylvania can be viewed at best as well-intentioned coercion. As for the Northern peace movement, it is obviously difficult to prove the counterfactual of what impact a Confederate victory at Gettysburg would have caused. However, it should be noted that those same “peace” Democrats anointed the Army of the Potomac’s favorite general, George B McClellan, as their candidate during the 1864 Presidential campaign, and Union soldiers overwhelmingly voted to return Lincoln to office, and finish the war.

All of this is to say that it would be nothing less than extraordinary for the Gettysburg campaign to end in Confederate victory. Yet, the Army of Northern Virginia had indeed proven itself to be an army perhaps capable of accomplishing the seemingly impossible, marching barefoot, launching successful attacks against greater numbers, and operating on such a shoestring that comparisons to Washington’s army at Valley Forge are not inappropriate. Despite the fact that most of the men were drafted, and many would ultimately desert the army whenever possible, morale amongst the Confederates was seen as extraordinarily high. Perhaps, this a reflection of the clarity of the army’s mission: to defend their way of life, as they saw it, to protect the social structure that was founded ultimately on slavery. Just as it was in the Confederacy as a whole, the officers were by-and-large planters (with the exception of the self-made businessman, controversial general, and ultimate founder of the Ku Klux Klan Nathan Bedford Forrest), while the soldiers were of the poor, landless whites. A veritable army of slaves followed the Army of Northern Virginia, as unpaid laborers and body-servants to officers, and it is thought that over a thousand escaped freedmen and slaves were enslaved or re-enslaved by the Army as it moved North.(5)

(5) https://www.theroot.com/did-black-men-fight-at-gettysburg-1790876264

Just as the Confederate armies represented a microcosm of one American society, the oft-defeated but never-destroyed Army of the Potomac represented another. Whereas the agricultural society of “King Cotton” cleanly dropped all people into one of three incredibly unequal positions, the Army of the Potomac was stitched together from whole different cloth, it seemed. The unfortunate XI Corps had the nickname of “the Dutchman” due to the preponderance of Germans in the unit. Many men of the army didn’t even speak English. The 39th New York regiment, likewise, was given the moniker “the Garibaldi Guard” being a largy immigrant Italian unit and wore red shirts into battle like their compatriots in the home land.(6) The famous Irish Brigade, made up of New York and Pennsylvania men exclusively, found praise from enemies and comrades alike at the battles of Antietam and Fredericksburg.(7) They would do so again at Gettysburg. While most of the men in the army were volunteers, many enlistments would be running out throughout the Gettysburg campaign, and soon drafting would begin in earnest throughout the North, a process that had already begun in the Confederacy the year before to much controversy. The ethnic, linguistic, religious diversity of the Army of the Potomac was clear and obvious in the men who made it up, and at this point in the war, had mostly volunteered for it. The diverse makeup of the men was reflected in the organization of the leadership.

(6) https://www.secretpriceofhistory.com/the-garibaldi-guard-1861-1865.html

(7) https://www.nps.gov/articles/irish-soldiers-in-the-union-army.htm#:~:text=Meagher's%20Irish%20Brigade%20was%20composed,Potomac%20throughout%20the%20entire%20war.

Whereas personal squabbles and disagreement over strategy troubled the officer corps of the Confederates constantly (with men like Braxton Bragg and DH Hill typically at the center of them), Robert E Lee and his staff officers were long-serving, with death rather than dismissal being the typical end of a Confederate general. Not so in the army of the Potomac, where command was oftentimes a political decision to keep the tenuous alliance of the brand-new Republican party from splintering. Only one general had fought more than one battle as its commander, that being the hot-headded logistical genius George McClellan. A difficult relationship with Abraham Lincoln led to his firing, even after instilling pride and discipline into the Army of the Potomac after its humiliating defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run. McClellan, a Democrat, was also known to greatly value the lives of his men, and ensure that living conditions were as humane as possible. He was not known as an aggressive commander, however, regularly mentally inflating the size of enemy forces, moving slowly and cautiously against the more mobile Confederates. While some of this slowness can also be attributed to the immense size of the Army of the Potomac (which at times would swell to over 120,000 men in aggregate), Ulysses Grant would prove that the Army could move as quickly or quicker in pursuit as its seccessionist foes. George McClellan was undeniably the most popular commander with the men, and his repeated firings were not welcomed by them.

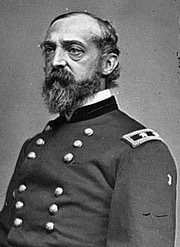

The man in command of the Union army at Gettysburg was George Mead, a Pennsylvania man, was known as a competent division and Corps commander, who nevertheless had the reputation of an unpleasant, annoying, and irritating man, would ultimately have the nickname of “Old Snapping Turtle.” His portrait may provide insight into why.

While the men whose units he commanded regarded him with respect, if not the love and admiration that George McClellan inspired, they were decidedly in the minority. Most of the men of the Army of the Potomac had little idea who this Meade fellow was, aside from an unknown officer with few political connections to grease the wheels for him -- Meade had been as surprised as anyone by the appointment. Yet one person, certainly, at least recognized Meade when given the news of his promotion; none other than Robert E Lee, reflected on the appointment by saying, “General Meade will commit no blunder on my front, and if I make one he will make haste to take advantage of it.”(8)

(8) Foote, 464.

To students of military history, Robert E Lee is a known name. George Meade, on the other hand, is something of a footnote. He had all the makings of a commander who would soon be fired after the defeats that plagued the Army of the Potomac for over a year now. Yet Meade would remain commander of the Army for the rest of the war, and avoid the disasters that had plagued it thus far in its history. Prior, as a divisional commander, Meade had the distinction of leading his men in an unsupported breakthrough of the Confederate right at Fredericksburg, commanded by Stonewall Jackson. Bloody hand-to-hand fighting ensued. When Confederate reserves threatened to drive the Union forces back, ineffectual Union attacks alleviated no pressure on Meade’s men. Surrounded on three sides, they were forced to withdraw. A furious George Meade would, according to the official record, later profanely berate his Corps commander for not supporting the attack in force. George Meade would be promoted to a Major General following this action, but remained angry for weeks. Many of the men that left him nearly surrounded would be his subordinates during the coming battle.

During an otherwise one-sided defeat for the Union(9), the incident is indicative of the Army of the Potomac’s approach to warfighting, the cause of the Union, and the attitude of the men doing both. The men of the northern armies were more numerous, with far fewer professional soldiers in the ranks of commissioned and noncommissioned officers. Whereas Confederate military leadership was mostly Virginian, mostly professional soldiers, and almost exclusively West Pointers, the Army of the Potomac had few professional soldiers, and many, many business leaders. Generals John Reynolds, Winfield Hancock, John Buford, and George Meade, West Pointers and professional soldiers all, were decidedly in the minority, and whereas these men were highly respected by the rank-and-file for their reputations, aggressiveness, and skill in combat, most of the leadership surrounding them were made up of relative novices to soldiering. Unlike the Army of Northern Virginia, which seemed to live or die based on its aggressive, against-the-odds assaults, the Union army in the east might make a piecemeal advance, or hold against Confederate assault as they did during the Seven Days, only for concern over supplies, casualties, and reinforcement to override any desire to go over to the offensive. The paradox of giving up ground in order in order to avoid heavy casualties in the short-term, while also extending that same conflict and ensuring more casualties medium to long term, is precisely the calculus of a leadership class of relative novices, concerned about their respective reputations, and in full knowledge that underperforming officers were regularly fired. No one knew this better than George Meade, who was the army’s sixth commander in just over a year.

(9) The Battle of Fredericksburg involved Union troops repeatedly charging uphill against entrenched and fortified Confederate lines. Except for Meade’s breakthrough, all other attacks failed utterly against accurate rifle and artillery fire.

Whereas the leadership of the army seemed to be in constant flux, the soldiers of the Republic remained committed to the cause, professional, and probably as well-trained as any other volunteer army on the planet at the time. Whereas an entire corps of Confederates would advance over Cemetery ridge during the carnage of Pickett’s charge on July 3rd, 1863, and be repulsed after a single attempt, multiple corps of the Union army attacked the fortified positions of Marye’s Heights at Fredericksburg, reformed doggedly, and tried again, under withering fire. While the battle of Fredericksburg was undeniably a Confederate victory, very few armies could withstand such a pounding and then fight again another day, let alone reform itself and retreat in an orderly fashion.

Even with all of the advantages of numbers and material, the Army of the Potomac had found victory difficult to achieve. A roster of more than a year’s worth of bloody defeats harangued the army, and a culture of back-stabbing, reputation-seeking officers plagued the high command. Heading into the battle of Gettysburg, author Michael Shaara described the men of the Army of the Potomac as having lost faith in their officers, but not in themselves. An ethnically, linguistically, religiously diverse army, made of up men from all over the Union states and including some Southern Unionist men, led by leaders mostly new to command or to the army life itself, were being pulled North to defend Washington and face “Mars Robert” E Lee once again. Yet this time, notes Shelby Foote in his description of the Army’s pursuit of Lee in late June, the sense among the ranks that defeat on their own ground, in defense of their own homes, was unthinkable. The stakes seemed to be never higher.

Other researchers have undoubtedly discussed the specifics of the battle elsewhere, so there is little point in discussing a play-by-play of the narrative of events. Suffice it to say that George Meade made the counterintuitive decision to defend his ground with more troops on the field, and let his corps commanders fight the battle with little interference from his headquarters. At points this strategy almost led to disaster (Dan Sickles was nearly court-martialled for his blunder into the Peach Orchard for example), but more often it let the gifts of individual commanders, such as Winfield Scott, to shine in something like independent command. By the end of the battle, the Confederate army had lost a third of its number, the Union almost a quarter. After July 3rd there would be very little fighting, and after the Confederates withdrew south, Meade ordered a pursuit so slow, he had to defend his reputation for the rest of his life. There would be some skirmishes and cavalry battles for the next few months, but there would be no major battle in the region until Ulysses S Grant took command of all Union armies, and launched his Overland campaign in May of 1864.

So, it's logical to ask the question, why is Gettysburg considered the “turning point” of the war. Historians ought to avoid the phrase in quotes, but Gettysburg represents such a phenomenon. The Confederacy was in the ironic position of winning tactical victories in the land between Washington, DC and Richmond, VA, while it was essentially being dismantled in the West. With the stunning Union victories at both Vicksburg, MS and at Gettysburg, PA, the war would indeed go on, and decidedly not end in a diplomatic negotiation or ceasefire. The Confederates had gambled everything and lost. Lee’s army would struggle to feed, clothe, and provision itself for the next 22 months of war, fighting hard, but being ground down in increasingly bloody encounters. But again, if the course of the war was clear, why did it continue? Both Robert E Lee and General James Longstreet, his chief subordinate, offered their resignations, both essentially stating that they thought the Southern cause lost. Yet Jefferson Davis refused both outright, and the human meatgrinder known as the American civil war continued to operate -- it is still the bloodiest conflict Americans have ever fought.

At least two visions of America strove with one another on those Pennsylvania fields, and while one in fact did go down in defeat (that being a slave-owning, highly agrarian, remarkably stratified, calcified oligarchy almost reminiscent of the way of life people came to America to escape from), that vision was hardly killed there, nor was it defeated when Lee finally surrendered in April 1865. Reconstructionist efforts, including the military occupation of the South, ended without completion in 1877, and the old Southern leadership began erecting monuments to generals and Confederate soldiers, romanticizing the war via “Lost Cause” revisionism, and returning freed slaves to a state of servitude at the bottom of that three part social hierarchy via the twin hydra’s head of Jim Crow laws and the sharecropping system. Legal slavery did not return, but its practical equivalent did, and the fight for true equality and civil rights for the children of freed slaves would begin again just as the last Civil War veterans were dying in the 1950s. Many would say that the fight continues to this day.

I am among them. Gettysburg is important because it is a part of that ongoing, seemingly perennial, fight, which at its heart really is about freedom, but also what kind of country the US will be: oligarchic, calcified, Protestant, and white supremicist or democratic, diverse, a polyglot of identities striving with one another, finding union only in fractiousness. Gettysburg is important, because that fight, that great conversation, still is not finished.