Peter Cox

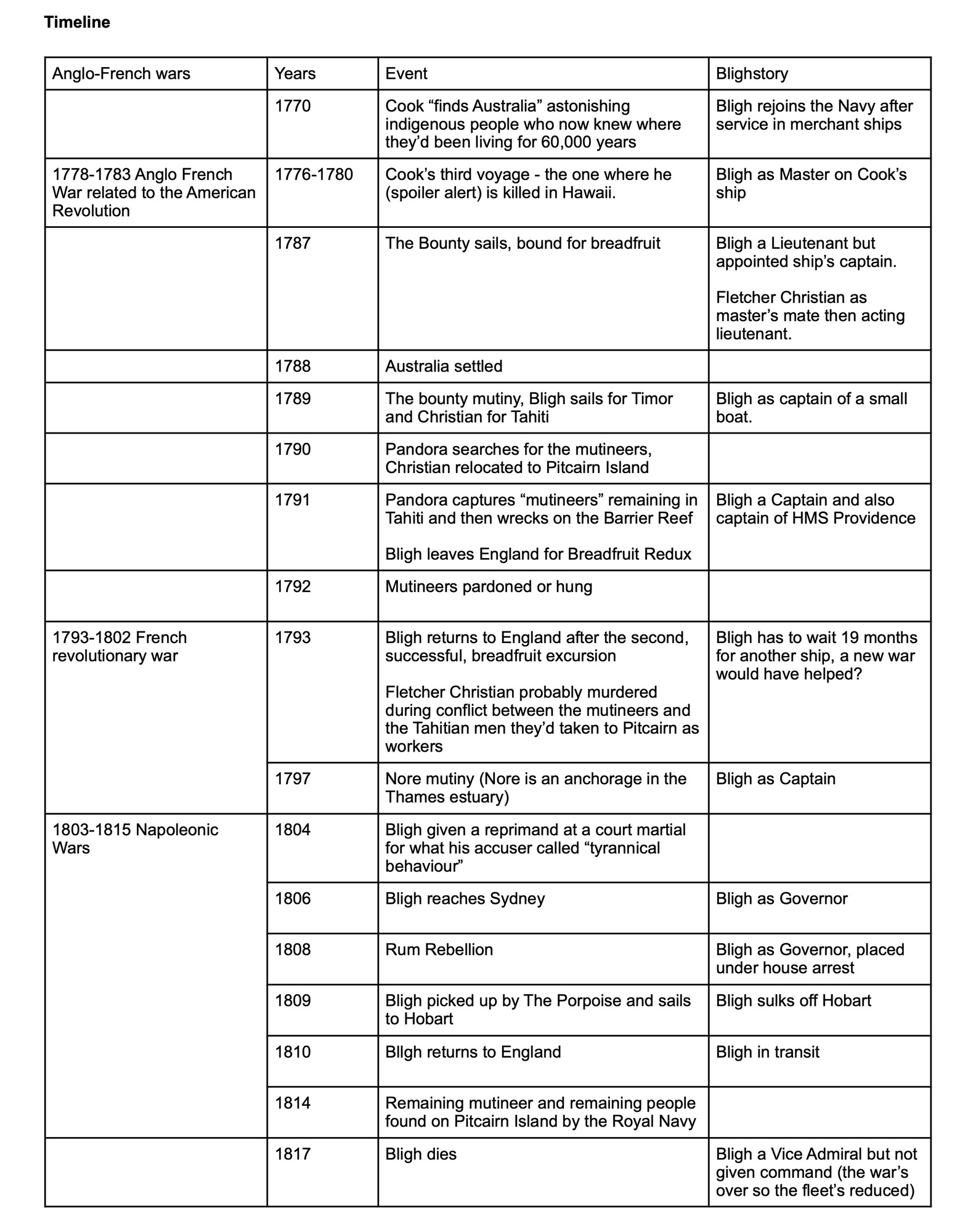

A timeline of Bligh's history

If you’ve ever wondered how many mutinies it takes to get promoted sideways out of trouble, the answer is three. Because William Bligh is a prime example of the problems you get when you take a skilled practitioner and make them a people manager.

Signed to the Royal Navy at the age of seven he actually went to sea at 16 as a seaman waiting for a slot as a “young gentleman” midshipman. Signing on years before actually going to sea was common practice at the time as a way of generating time in service for later advantage in competing for promotion. It’s the kind of minor corruption endemic in the system of patronage, fraud and theft that characterised systems of government service at the time. But who are we to criticise :)

Bligh was a career sailor and, very early in his career, was marked out for roles emphasising navigation, mapping and ship management. This included appointment as sailing master - basically the senior navigating officer - on Cook’s third (and final) voyage to the Pacific.

While Bligh’s navigation to Timor after being cast adrift shows impressive skills it remains miraculous that weather, thirst, starvation and infighting didn’t kill the party en route.

So, he’s a hell of a seaman. How’d he get the gigs? Skills are part of it, also patronage! The time with Cook brought him close to Sir Joseph Banks, the influential aristocrat, botanist and president of the Royal Society (the key British science organisation of its time). And noted pants man. Banks’ influence got Bligh the job on the breadfruit cruise and also helped him get his later job as Governor of New South Wales. So that’s patronage.

Fraud and theft? All that stuff about the cheeses and coconuts is a reference to the fraud in the Naval establishment that had the various middlemen - from suppliers to chandlers to ship captains to their senior crew - “clipping the ticket” as goods passed through their hands. Readers of Patrick O’Brian’s Maturin/Aubrey series or C.S. Forester’s Hornblower series will be familiar with the Captains’ battles to make sure their ships left harbour with fresh food and water - not the condemned garbage from the back of the warehouse that would leave their crews rotten with scurvy and dying of thirst mid ocean. Did Bligh really do that? More research required, but the scriptwriters assembled every example of every type of rough behaviour in the Royal Navy to make their case against Bligh while Fletcher Christian got to be loved up (with the ladies of Otaheite) and heart hurt by the Captain’s insults.

The script writers had plenty of torture porn with whipping around the fleet, keel hauling (a capital punishment), flogging, reduced rations and water, exposure at masthead or in the rigging . . . they only missed “grog stoppages”, where the sailors were not allowed their daily allowance of rum and water. Perhaps it was too soon after prohibition for drinking?

But even if the screen writers laid it on pretty thick, you can’t deny that Bligh suffered three mutinies. Bligh’s first mutiny was the subject of the movie, set in 1789. But, showing what absolute horseshit the end roll is, Bligh was captain during a second mutiny during the infamous 1797 Nore and Spithead mutinies that also feature in O’Brian and Forester books. These were more about conditions on board ships in home harbour, lack of pay etc so Bligh wasn’t specifically responsible for that.

There is no way, as the end roll suggests, that the Mutiny on the Bounty created a new relationship between officers and men and set the Royal Navy up for future success. The mutinies that followed showed that the harsh service, ferocious discipline and god-like powers of the senior officers did not change until well into the 19th century. Dip into C.S. Forester’s book Lieutenant Hornblower (or watch the BBC Series with Ioan Gruffudd) for a sense of the hell a Captain with powers of life and death can make a small, crowded ship.

Bligh’s final mutiny was in the colony of New South Wales in 1808. He was sent to put an end to the endemic corruption of the NSW Corps, the soldiers sent with the First Fleet. The “Rum Rebellion” in 1808 came when the troops and some settler supporters rose up against Bligh’s “tyranny” - his attempt to follow his instructions and stop the profiteering and commercial enterprise of the troops and some settlers trying to set themselves up as what a more recent politician would call a “bunyip aristocracy”. In a repeat of the post-Bounty, anti-Bligh agitprop, the NSW mutineers did a great job blackening Bligh’s name with accusations of his outrages against their sensibility and some lovely propaganda of him being dragged out from under a bed where he was alleged to be hiding during the takeover. While the NSW Corps was disbanded, mutineers (gently) punished and the rum trade and rampant colonial profiteering suppressed (somewhat) Bligh didn’t get another major assignment. He knew his trade but, after only three mutinies and a couple of courts martial (acquitted), senior Royal Navy management decided his people skills were not up to snuff. He was parked as Vice Admiral of the Blue when he was benched.

The focus here is on Bligh rather than the mutineers largely because he’s the most fascinating character in real life - a brilliant navigator and sailor but not someone you’d want in your work team or as a boss - and his story is deeply intertwined with early Australian history. The mutineers are less interesting in life and left a troubling legacy on Pitcairn Island (covered by Rich).

Bits and pieces

Like most war movies, everyone is too old. Bligh was only 33. Fletcher 25. Byam - Peter Heyward in life - was 16.

After immersion in C.S. Forester and O’Brian - all the ceilings were too high in the internal ship shots on Bounty. Clark Gable was 1.85m - around six foot - and would surely have had to crouch to get around below deck. After the Mary Rose rolled over in 1545 the Royal Navy was more particular about engineering to avoid top heavy ships. High ceilings across three or four decks, especially with a couple of gun decks full of artillery, move the centre of gravity up. I often look at cruise ships in Sydney Harbour and wonder at their massive height but apparently shallow draft. Must be a lot of weight in engines, fuel and stuff below the waterline.

You can’t ignore that this whole Bounty breadfruit enterprise was to prop up enterprises relying on enslaved labour. Cheap, high yield food found in one part of the tropics transplanted to another part of the tropics so that a convenient food source would be available without diverting arable land or enslaved labour. The enslaved people didn’t like the breadfruit so the successful second cruise Bligh undertook to transplant the trees didn’t work out despite the successful delivery. I’m not across the detail of Caribbean cooking but this reference suggests that St Vincents is the place where breadfruit was, and remains, a hit. I’ve only eaten Caribbean a couple of times in London so IDK. But it is interesting that favourite traditional foods often had their origin as foods of last resort or poverty. Corned meat in Australia, for example, remains popular but only exists because salted meat was the only meat that would last in our heat before canning or refrigeration. Haggis looks like the last act of a starving population to me. Presumably collard greens and grits - the foods of oppression - in the American South?

In Tahiti Byam tries to explain the relative value of a nail and a coin but the Chief is unconvinced. Theft of goods, especially metals, from ships trafficking through the Pacific was a major source of conflict between locals and visitors.

It’s a bit difficult to watch the lust Tahitian women show for visiting sailors in the movie when you’ve read Alan Moorehead’s The Fatal Impact: The Invasion of the South Pacific, 1767-1840. Which goes into the way trading sex was actively used across the Pacific to get valuable goods, especially metal, from visiting ships. The Fatal Impact, a mandatory read at school around 14, completely rewired my adolescent brain about European colonisation in my region. Kind of surprising the conservative state government of that time let that happen.

The good old Barrier Reef. Cook ran into it. The Pandora ran into it (not with Bligh on board). If we don’t have Brit’s crashing into the reef trying to get up to the Torres Strait we’ve got Dutchmen crashing into Western Australia when they're riding the roaring forties and don’t turn left in time. Navigation’s not that exact a science even with timepieces. Which makes Bligh’s feat of navigation to Timor and not hitting the reef or running aground in the Torres Strait even more astonishing.

Rich Stephens

Trivia

Roger Byam was a fictional character based on Peter Heywood – a 15 year old “young gentlemen” aboard the Bounty; similar to the role of cadets or officer candidates in modern navies.

Chief Hitihiti has a fairly prominent small pox vaccine scars on his upper arm.

Bligh wasn’t on the Pandora when it visited Tahiti in search of the mutineers.

Research and Talking Points

Breadfruit – the HMAV Bounty was to sail to Tahiti to obtain breadfruit saplings that were to be distributed and transplanted to British colonies in the Caribbean – primarily Jamacia. They were trying to find an inexpensive and nutritious way to feed the large number of slaves who worked the island’s sugar plantations. A single breadfruit tree can produce between 50 and 250 fruits per season for 50 years. A mature fruit weighs about 10 pounds (4.5 kg) and contains about 100 calories per 100 g serving. After the Bounty expedition, Bligh was once again tasked with brining Breadfruit from Tahiti to Jamaica – this time successfully – arriving in Jamaica in 1793 with 678 breadfruit trees.

Keelhauling – A form of punishment whereby a sailor is dragged – bow to stern – underneath a ship. The barnacles and other marine organism that grow on the hull will cut the person, possibly becoming infected and scarring them.

Press Gangs - groups of soldiers or sailors sent out to enforce naval or military service on able bodied but unwilling men, often by violent coercion. The press gang, a group of 10 - 12 men, led by an officer, would roam the streets looking for likely 'volunteers'. Merchant seamen were particularly prized as they already had seagoing experience and needed less training.

British Classes – The Royal Navy of the time adhered staunchly to the British class system. The dividing line between officers and enlisted sailors aboard ships was defined by much more than mere rank and time in service. The officers were made of gentlemen (in the most titled sense) of upper-class families. The enlisted, the lower classes. (the paper linked below makes an interesting case that in certain “Admirals of the Fleet” families, progeny were essentially raised to become naval officers.)

Courts-Martial – Ten of the Bounty prisoners captured by the Pandora were court-martialed for mutiny. Four were acquitted based on Testimony from Bligh that they had been detained against their will. The other six were found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. Two of the men – Heywood (the lone officer-class defendant) and Morrison were recommended to “his Majesty’s Royal Mercy” and was pardoned. Another, Muspratt, was also pardoned.

On the morning of October 29th, 1794 three of the mutineers – Burkett, Millward and Ellison – were hanged by the yardarm aboard the Brunswick in Portsmouth harbor. The prevailing feeling that men with patronage or connection could live, but those without were doomed.

Warning – this next section deals with sexual abuse of young girls. I won’t go into many details here, but there are links to several articles below if you would like to learn more about this, what I can only call, tragedy.

Pitcairn Islands Today and Sexual Assault Trials – Today, Pitcairn Island is the least populated national jurisdiction in the world – with only 47 permanent inhabitants (2020). The inhabitants are a biracial ethnic group descended mostly from nine Bounty mutineers and several Tahitians (six men, 11 women, and one baby girl.) Pitcairn has been the subject of multiple instances of widespread sexual assault since at least the 1950s, with the 2004 trial being the most recent. Seven men (1/3 of the island male population) faced 55 charges of sexual abuse against children. Six were found guilty of raping and indecently assaulting girls as young as 12 on the island – including the town’s mayor, Steve Christian.

One quote from an article in the Independent shows up in multiple articles, and it really encapsulates the issues:

“Supporters are arguing that the entire affair is based on a misconception. They claim, variously, that the age of consent on the island has long been 12 or 14, and say that if girls become sexually active earlier than in Western societies, it stems from their part-Polynesian ancestry and should be respected.”

The tragedy of the Mutiny on the Bounty reverberates through history and into today.

Works Cited

Ridiculous History: Breadfruit, the Bounty and the Birth of Globalization | HowStuffWorks. Accessed 08/05/22.

Captain Bligh's Cursed Breadfruit | Travel| Smithsonian Magazine. Accessed 08/05/22.

Press gangs and Royal Naval recruitment or impressment (welcometoportsmouth.co.uk). Accessed 08/05/22

Turner, George. Social Mobility in the Royal Navy during the Age of Sail: investigating intergenerational social mobility in the Royal Navy between 1650-1850. The London School of Economics and Political Science. Economic History Student Working Papers. No: 008. SWP-008.pdf (lse.ac.uk)

The Court-Martial of the Bounty Mutineers: An Account (famous-trials.com). Accessed 08/08/22

Pitcairn Islands - Wikipedia. Accessed 08/08/22.

Evil under the sun: The dark side of the Pitcairn Island | The Independent | The Independent. Accessed 8/8/22

6 Are Guilty in Pitcairn Island Sex Abuse Case - The New York Times (nytimes.com)v 6 Are Guilty in Pitcairn Island Sex Abuse Case - The New York Times (nytimes.com). Accessed 08/08/22.

The paradise that's under a cloud | The Independent | The Independent. Accessed 08/08/22